Hormonal Mechanisms

Contents

Hormonal Mechanisms¶

Why?

Animals have a blueprint of behavioral actions that are each controlled by specific genetically-coded neural circuits. However, animals don’t (can’t) do all of their actions at once… at any moment in time, the intensity of each behavior must be modulated to match the demands of the animal’s external environment (resource quality, social cues, etc) as well as internal environment (metabolic demands, internal state, etc).

Without genes and neurons, hormones would do nothing. In other words, they modulate existing genetic and neural systems. Modulation can happen reversibly over relatively short timescales or irreversibly (usually “during development”).

The distinction among neurotransmitters, neuromodulators and neurohormones is very blurred 1.

Hormones can either be produced within an animal’s body or tranferred (often via ingestion) from their environment.

- endogenous¶

originating from within an animal’s own body

- exogenous¶

origination from the environment outside the animal’s body

Historical Context¶

Let’s start today with a discussion related to The Fantastical World Of Hormones With Dr John Wass.2

⏳ 10 min

Q1: This video raises a great opportunity to speak about the elephant in the room: animal experimentation. Experiments on non-human animals have played a significant role in our understanding of physiology in general, and hormones and behavior is no exception. As noted in the video, many of the early experiments-including the very experiments performed by Bayliss and Starling that were the inspiration for the term “Hormones” - utilized dogs (what is left out of the video is that Bayliss was actually a plaintiff in one of the first major protests against vivisection in modern biomedical research, precisely because of his use of dogs in this endocrinology research). Take a few minutes to discuss any apprehension or questions/concerns you may have regarding the use of animals in biomedical research.

Q2: How do Berthold’s experiment with the capons and von Halban’s experiments with guinea pig ovaries (the experiments that ended use of oophorectomy as treatment for neurological and psychiatric ailments in women) support a role for non-neuronal chemical signaling in biological function?

Q3: Why was harvesting “pink thyroid juice” from sheep a successful approach to treating disorders of hypothyroidism yet the same approach applied to treating reduced virility (with goat testis fluid) considered quackery?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

For behavior, hormone effects on the nervous system and neuron physiology are the main mechanism of action.

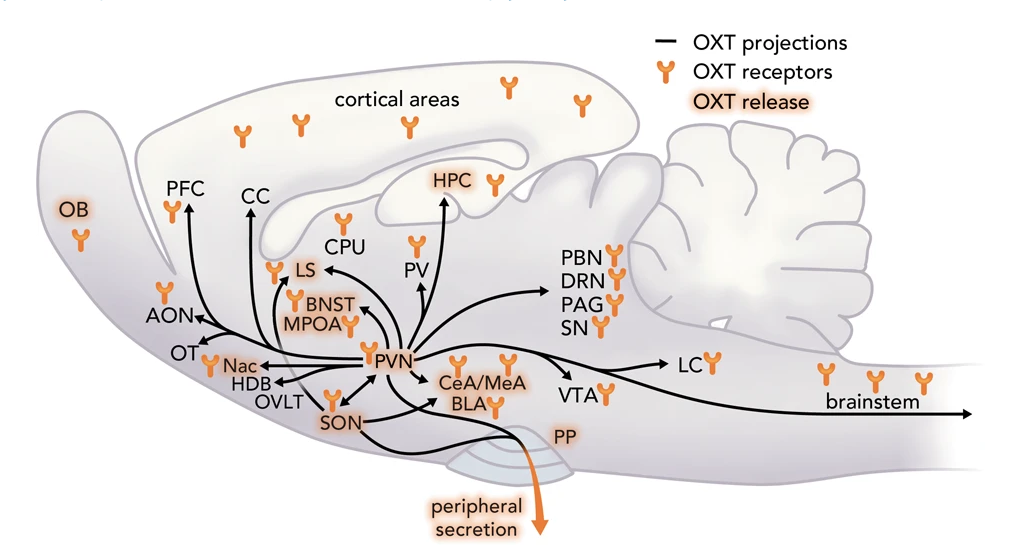

Some hormone circulation is even local to the brain (does not need to go through the blood to get to the brain). For example, neurons in the hypothalamus of the brain (specifically the paraventricular nucleus) produce oxytocin. These oxytocin neurons project widely throughout the brain, where they “dump” oxytocin onto neural circuits. Oxytocin then modulates neural processing.

Fig. 43 This scheme summarizes all available data from male and female including lactating rats regarding OXT neuronal projections, sites of OXT release, e.g., during stress exposure, mating, parturition, suckling, and OXT receptors within brain target regions, as outlined in detail in Grinevich and Neumann (2021)3. OXTergic projections originating from the PVN are depicted as black lines, connecting brain region where OXTR expression has been detected. Brain regions where OXT release has directly been shown by microdialysis are highlighted.¶

General Mechanism¶

Steroid hormones are lipid soluble while non-steroid hormones (amino acid based - proteins, peptides, and derivatives) are water soluble.

Hormones generally do nothing by themselves. Hormone receptors change genetic and physiological properties of cells when they are in contact with their specific hormone molecule.

Hormones circulate in the blood and extracellular fluid of the body.

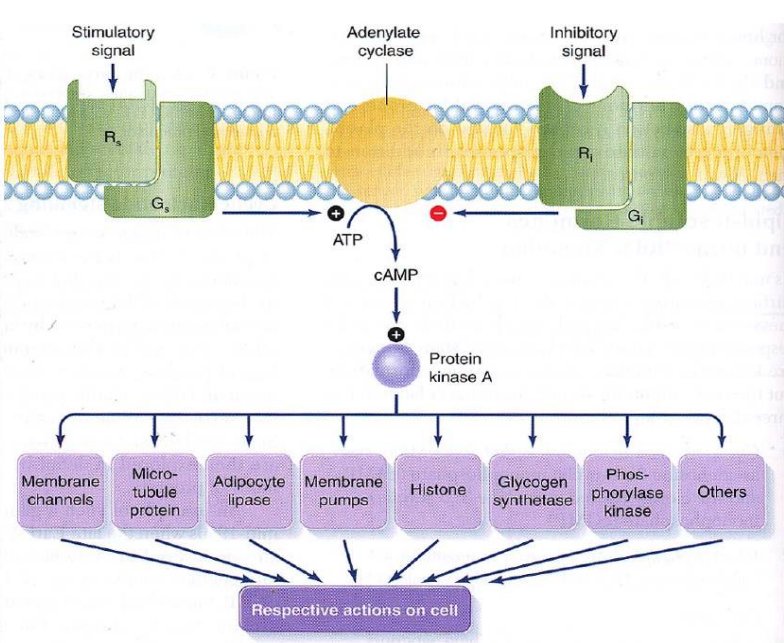

Fig. 44 Cartoon of a common hormone mechanism of action. Hormone molecules bind to specific receptors on the cell’s surface (unique to that hormone). Hormone binding triggers a conformational change in the receptor protein that causes G-proteins to bind to adenylate cyclase proteins. When G-protein binds adenylate cyclase, cAMP is produced, which then triggers a wide variety of protein kinases to act on their specific downstream targets. R = hormone receptor, G = G-protein, ATP = adenosine triphosphate, cAMP = cyclic adenonsine monophosphate¶

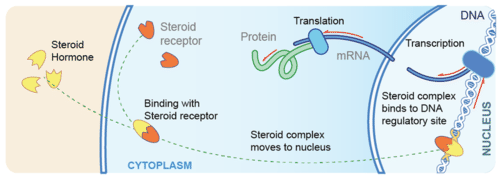

Fig. 45 Cartoon of a common hormone mechanism of action. Hormone molecules bind to specific receptors inside the cell. In this case, the hormone and its receptor form a transcription factor that alters gene expression directly. Image from cK-12.¶

The following questions should prime you to think about hormone mechanims of action on behavior and check your current understanding of the concept.

⏳ 10 min

Q4: The same hormone can be stimulatory (excitatory) for physiological/molecular processes in some neurons while simultaneously suppressive (inhibitory) in other neurons. True/False? Briefly explain.

Q5: Why are relay molecules such as cAMP necessary for water-soluble hormones (but not lipid-soluble hormones) to affect gene expression?

Q6: What is the effect of a hormone if there are no receptors for the hormone?

Q7: How could hormones modulate the membrane potential of neurons?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Case Study: Aggression in Mice¶

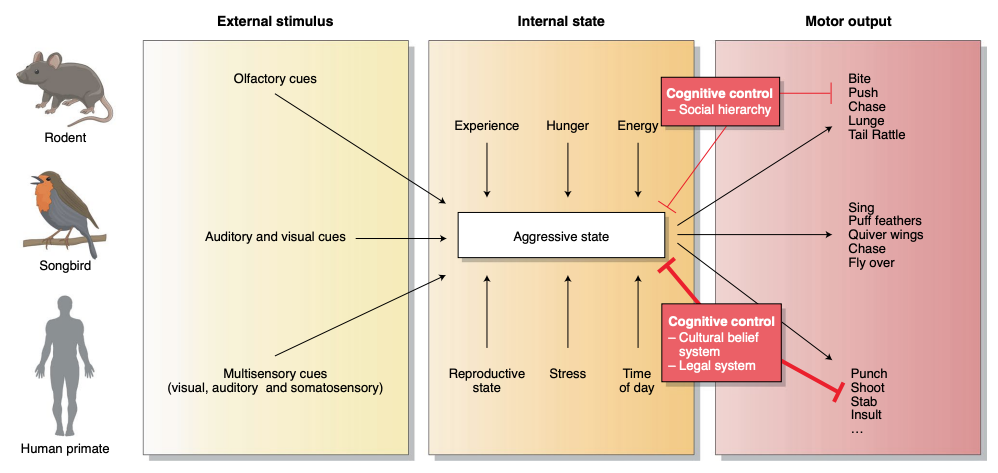

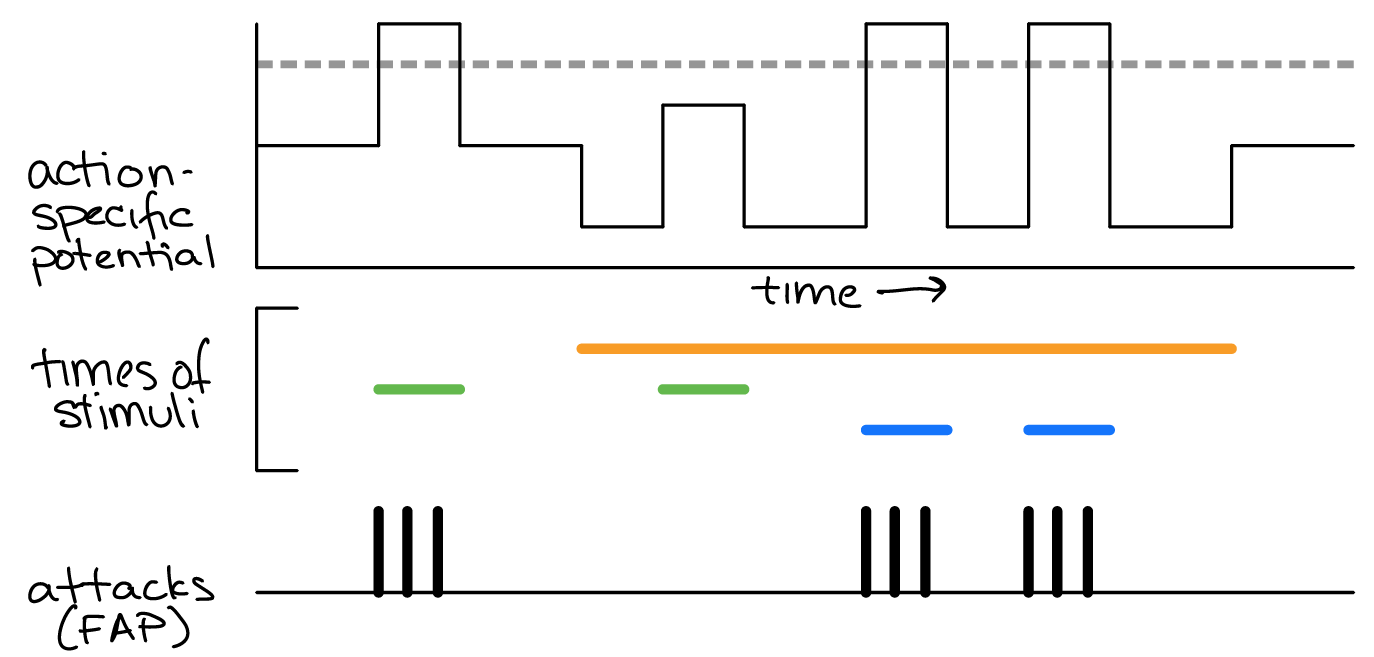

Aggression is a social behavior essential for securing resources and defending oneself and family. Many animals have aggressive FAPs. Across animals, we find that the release of FAPs depends, not just on the presence of external sign stimuli (detected using sensory filters), but also on the internal state of the animal.

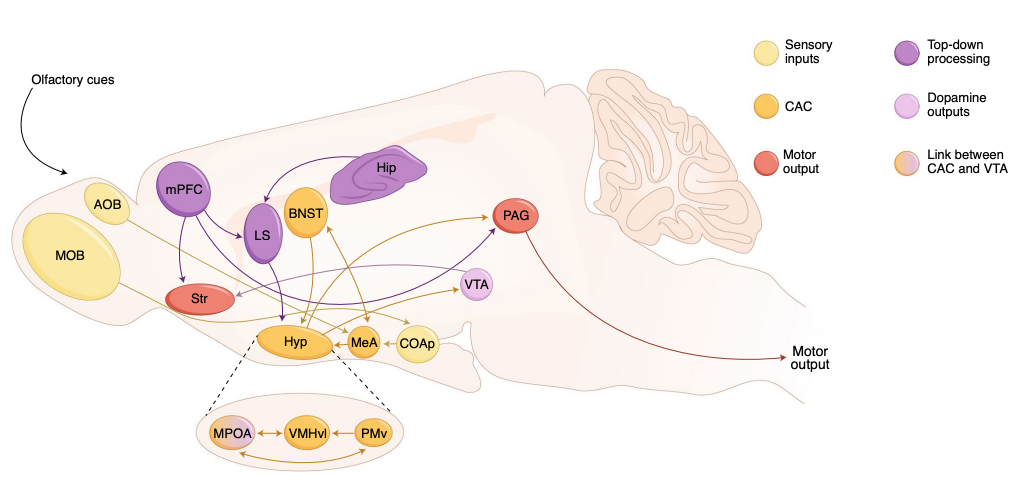

Regions of the brain in the core aggression circuit are more specialized for aggression: activating any of those regions evokes attack, often in a time-locked manner, while inactivating any of those regions impairs or even abolishes natural aggression. The fact that aggression can be triggered as well as blocked from each of those regions supports the idea that these regions form one integrated circuit.

The ventrolateral nucleus of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMHvl) is perhaps the best studied region for aggression in recent years, with the vast majority of the studies done in mice. Electrical stimulation or pharmacological manipulation in the VMHvl can elicit aggression in cats, chickens, opossums and monkeys. In male and female mice, optogenetic activation of VMHvl cells, especially those expressing estrogen receptor alpha (Esr1), elicited time-locked attack toward both natural (other mice) and suboptimal targets (gloves filled with water or air; or socially inappropriate attacks at conspecifics). Upon male-intruder introduction, VMHvl cells show an elevation in baseline activity, which is sustained throughout the duration of the intruder’s presence and minutes after removal of the intruder. During male–male investigation and attack, VMHvl activity increases further, and then returns to the elevated baseline at the offset of the behavioral episode. Thus, the VMHvl cells appear to carry information regarding aggressive arousal state, aggression-provoking sensory cues and the motor execution of attacks.

—Julieta Lischinsky and Dayu Lin (2020)4

Fig. 46 Neuroanatomical pathways for aggression in mice. Yellow indicates regions for processing sensory inputs; orange indicates regions belonging to core aggression circuit (CAC); red indicates regions relevant for motor output; purple indicates regions for top-down control and lilac indicates regions where dopamine neurons reside. AOB, accessory olfactory bulb; MOB, main olfactory bulb; CoAp, posterior cortical amygdala nucleus; Hyp, hypothalamus; MPOA, medial preoptic area; Hip, hippocampus; Str, striatum. From Neural mechanisms of aggression across species, a by Julieta E. Lischinsky and Dayu Lin (2020).¶

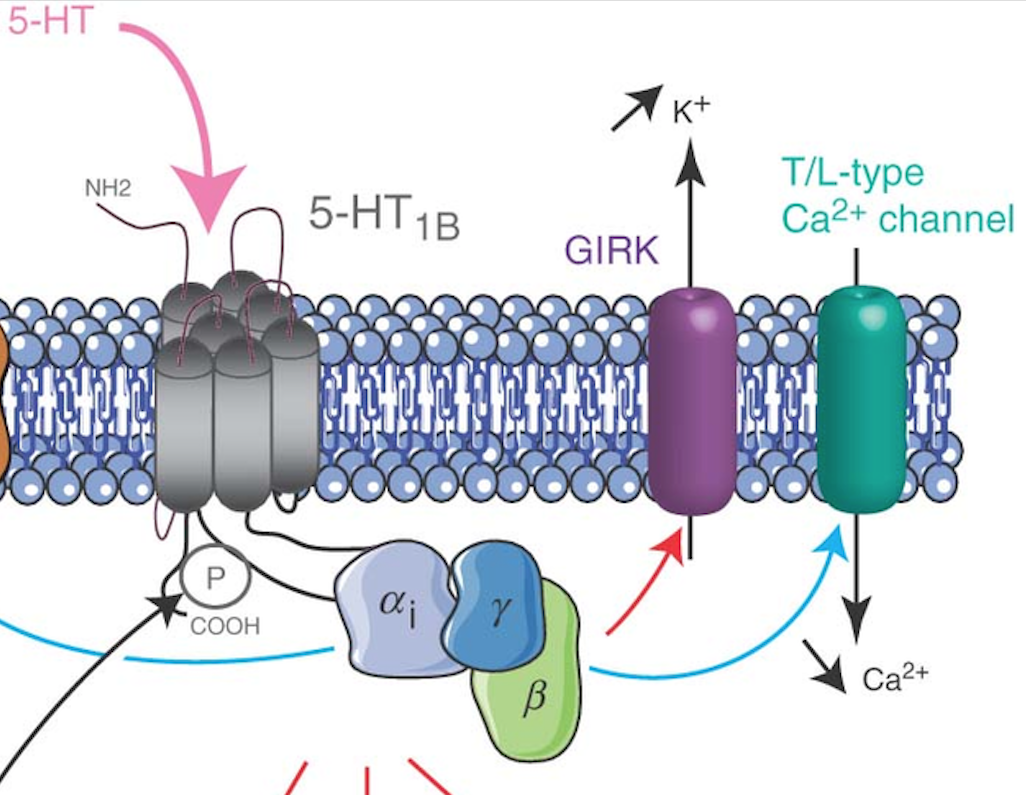

Serotonin is a molecule that acts both as a neurotransmitter and as a neurohormone. In the context of aggression, it is one of the hormones that modulates the motivation (“readiness”) to be aggressive. Neurons in the VMHvl express serotonin receptors. One mechanism of action for serotonin (via the 5HT1B or 5HT1A receptor specifically) is a change in neuron membrane ion conductance4.

Fig. 47 Serotonin receptor mechanism of action on neuron membrane conductance. This serotonin receptor (named “5HT1B”) is G-protein coupled. One of its “downstream effects” is to increase potassium ion conductance and decrease calcium ion conductance.¶

⏳ 15 min

Examine the model in Figure 42 and use what you know about neural mechanisms to answer the following questions.

Fig. 48 A Lorenz model of behavior for a male mouse defending its territory. Top: action-specific potential across time (black). Middle: the time during which external or internal stimuli (orange, green and blue) were present. Bottom: time of attack FAPs.¶

Q8: Which “time of stimulus” color most likely corresponds to the presence of a dominant (threatening) intruder (versus a submissive) intruder? Why?

Q9: Which “time of stimulus” color most likely corresponds to the presence of serotonin in the animals? Why?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Case Study: Sexual Behavior¶

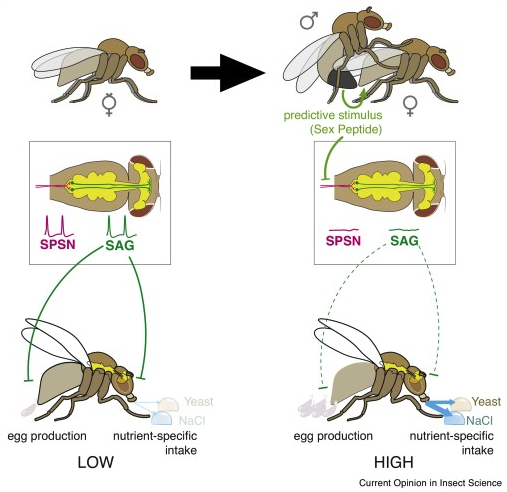

Behavior in virgin animals often differs dramatically from behavior in mated animals. In fruit flies, male gonads manufacture a peptide termed ‘sex peptide’ that gets transferred to females during insemination. Sex peptide provides a long-lasting signal that effects multiple mating behavior neural circuits in a female fly. For example, virgin females do not lay eggs and do not crave salt (NaCl) or yeast. However, after mating, females lay lots of eggs and crave/eat lots of salt and yeast (salt and yeast are necessary nutrients for egg production).

Fig. 49 Sex Peptide stimulates both egg production and anticipatory appetites necessary to support reproduction through the SPSN-SAG neuronal circuit. Left: virgin female. Right: sex peptide is transferred to the female during mating. The fly central nervous system (yellow) is shown from above within the boxed region. SAG and SPSN neurons are highlighed. SAG = sex peptide abdominal ganglion neuron (green); SPSN = sex peptide sensory neuron (purple). SPSN axon terminals synapse on SAG dendrites in the abdominal ganglion. SAG neurons send axons to the head ganglion. Sex peptide is sensed by neuron dendrites the uterus of the female. In the absence of sex peptide, SPSNs are active, meaning they continuously produce voltage spike events (green). SPSNs excite SAGs. SAGs inhibit egg laying and salt/yeast appetites.56¶

⏳ 10 min

Q10: In terms of the Lorenz model, sex peptide likely [ increases / decreases ] the action specific potential for egg laying behavior. (select one bracketed word to complete the sentence)

Q11: The drosophila nervous system must have gustatory (ie. taste) sensory filters for specific types of foods. What is the evidence from this case study that supports this statement?

Q12: Let’s say that the gustatory sensory filter is an excitatory command neuron for eating FAPs. Do you predict that the membrane potential response of the gustatory sensory filter is more depolarized or more hyperpolarized in the presence of Yeast in virgin females compared to mated females?

Q13: Why does the SAG neuron produce voltage spike events in virgin females, but not mated females? Explain in terms of both a hormonal and a neural mechanism.

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

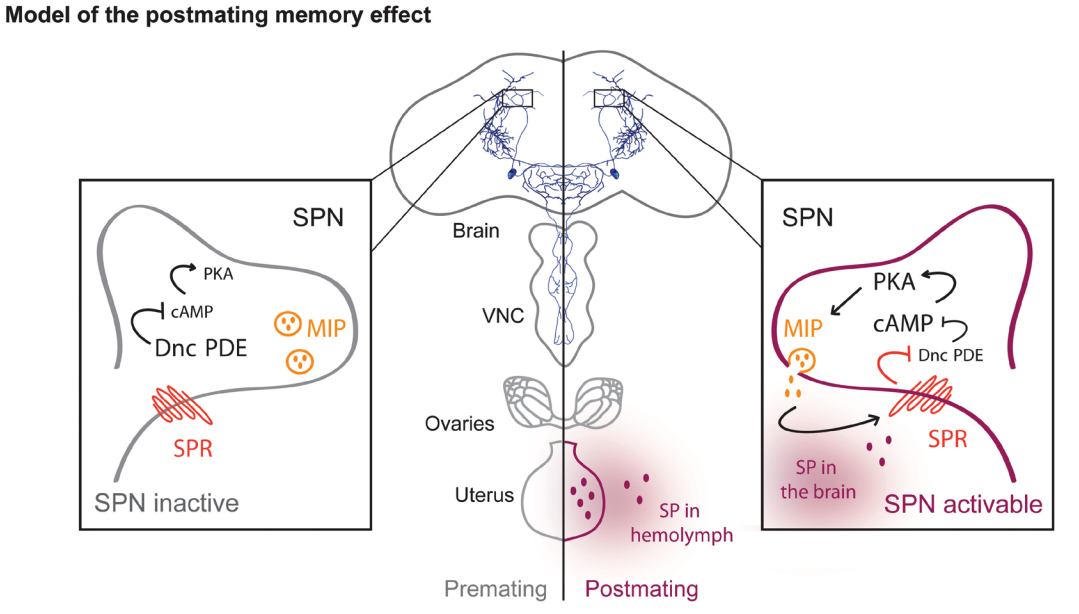

Sex peptide has LOTS of modulatory effects on the nervous system (in both females and males). Interestingly, sex peptide was recently shown to enhance long term memory of female fruit flies.

Fig. 50 Drosophila virgin females cannot form long-term memory. Upon fecundation, the sex peptide is transferred from the male testis to the female ovary. From there, the sex peptide reaches the brain and activates a pair of neurons that controls long-term memory formation. SPN = sex peptide receptive neurons in the brain; VNC = ventral nerve cord; MIP = myoinhibitory peptide (released from SPNs); Dnc PDE = Dunce phosphodiesterase that degrades cAMP; PKA = protein kinase A. PKA activity puts SPNs in an ‘activatable’ state for long-term memory formation. As a default state, Dnc PDE inhibits the cAMP-PKA pathway within SPNs, which inhibits long-term memory formation. PKA activation leads to the release of MIP, which increases the effects of sex peptide, further increasing long-term memory formation. 7¶

⏹️ STOP here for today

Additional Resources¶

A neuroendocrine basis for the hierarchical control of frog courtship vocalizations

Anita V. Devineni1 and Kristin M. Scaplen (2022) Neural Circuits Underlying Behavioral Flexibility: Insights From Drosophila. Front. Behav. Neurosci.

Focus on Modulation by Internal State Pick one hormone pathway/effect and share it at the next class.

Caroline B. Palavicino-Maggio1 and Saheli Sengupta (2022) The Neuromodulatory Basis of Aggression: Lessons From the Humble Fruit Fly. Front. Behav. Neurosci.

- 1

From Burrows, Malcolm, ‘Actions of neuromodulators ‘, The Neurobiology of an Insect Brain (Oxford, 1996; online edn, Oxford Academic, 22 Mar. 2012):

A neurotransmitter is a messenger released from a neuron at an anatomically specialised junction, which diffuses across a narrow cleft to affect one or sometimes two postsynaptic neurons, a muscle cell, or another effector cell. A neuromodulator is a messenger released from a neuron in the central nervous system, or in the periphery, that affects groups of neurons, or effector cells that have the appropriate receptors. It may not be released at synaptic sites, it often acts through second messengers and can produce long-lasting effects. The release may be local so that only nearby neurons or effectors are influenced, or may be more widespread, which means that the distinction with a neurohormone can become very blurred. A neurohormone is a messenger that is released by neurons into the haemolymph and which may therefore exert its effects on distant peripheral targets. It may differ only in degree from a neuromodulator in the extent of its action.Defining neurotransmitters, neuromodulators and neurohormones

A neurotransmitter is a messenger released from a neuron at an anatomically specialised junction and that diffuses across a narrow cleft to affect one or sometimes two postsynaptic neurons, a muscle cell, or other effector cell. Typically, a neurotransmitter acts directly on a postsynaptic neuron to cause a change in its membrane potential, although it may sometimes act through second messengers.

A neuromodulator is a messenger released from a neuron in the central nervous system, or in the periphery, that affects groups of neurons, or effector cells that have the appropriate receptors. It may not be released at synaptic sites, often acts through second messengers and can produce long-lasting effects. The release may be local so that only nearby neurons or effectors are influenced, or may be more widespread, which means that the distinction with a neurohormone can become very blurred. The act of neuromodulation, unlike that of neurotransmission, does not necessarily carry excitation of inhibition from one neuron to another, but instead alters either the cellular or synaptic properties of certain neurons so that neurotransmission between them is changed.

A neurohormone is a messenger that is released by neurons into the haemolymph and which may therefore exert its effects on distant peripheral targets. It may differ only in degree from a neuromodulator in the extent of its action. Those with restricted actions may sometimes be called local neurohormones to emphasise that their effects are localised.

These terms do not define rigid categories but rather the peaks in a continuum of effects. Some substances, such as nitric oxide (NO), can act as a transmitter but by virtue of their diffusibility might act on many cells, while substances such as octopamine can fulfil the requirements of all three definitions. A restricted but workable definition of neuromodulation (Kaczmarek and Levitan, 1987) suggests that it is ‘the ability of neurons to alter their electrical properties in response to intracellular biochemical changes resulting from synaptic or hormonal stimulation’. On this basis, neuromodulation can result from the actions of a substance defined in any of the three categories.- 2

The questions in this first section (in reference to the video you watched before class) were written by Dr. Laverne Melon for her Hormones, Brains, and Behavior course (BIOL 224).

- 3

- 4(1,2)

- 5

Eric Kubli and Daniel Bopp (2012) Sexual Behavior: How Sex Peptide Flips the Postmating Switch of Female Flies. Current Biology, 22(13): R520-R522

- 6

Samuel J Walkera, Dennis Goldschmidt, and Carlos Ribeiro (2017) Craving for the future: the brain as a nutritional prediction system. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 23: 96-103.

- 7

L. Scheunemann et al. A sperm peptide enhances long-term memory in female Drosophila, Science Advances (2019).