Escape

Contents

Escape¶

Considering escape behavior from all 4 levels of analysis.

⏳ 5 min

What is escape?¶

Q1: What makes an effective escape? In other words, what are the steps that need to happen and what overall properties should the behavior have? Can you think of some examples?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Simple behavior, complex computations¶

The most common escape behaviors are ballistic, stereotyped actions. Once they are initiated, their pattern cannot be modified. …These are more like reflexes than behaviors. BUT the neural circuits of escape are sometimes coopted by non-escape behaviors (we will look at an example in archer fish later).

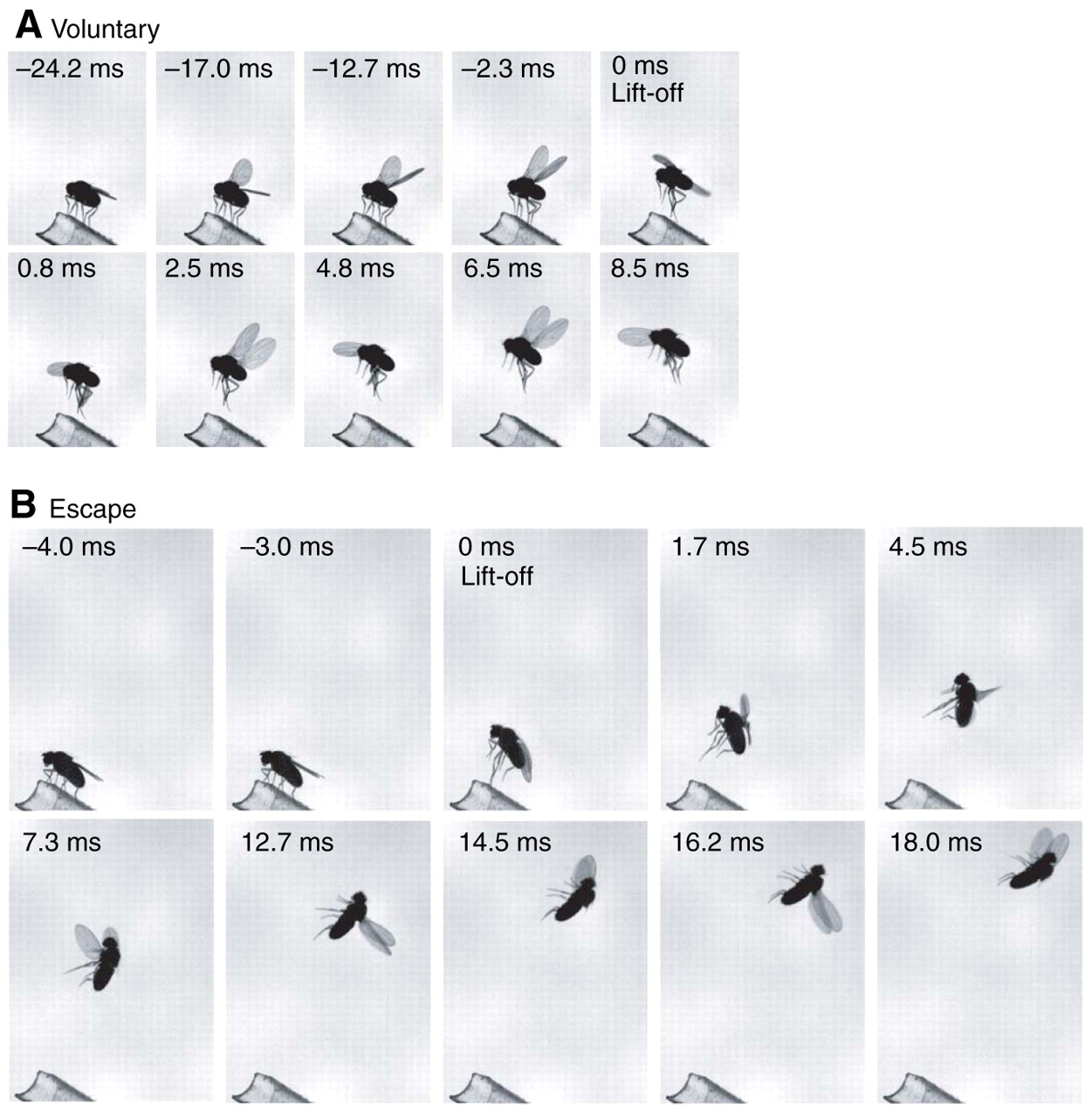

The following video (from Card et al 2008) depicts the escape of a fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, in response to a frisbee falling on a collision course with the fly (mimicking the “looming” visual stimulation that might be created by a predator or fly swatter). The disk approached from the right-hand side of the frame (left in one video) at 50 degrees from the horizontal.

The conditions depicted in the video are:

normal escape

without wings

without the jump legs

(through 6) normal escape

Using high-speed videography, Card et al found that approximately 200 ms before takeoff, flies begin a series of postural adjustments that determine the direction of their escape. These movements position their center of mass so that leg extension will push them away from the expanding visual stimulus. These preflight movements are not the result of a simple “feed-forward” motor program because their magnitude and direction depend on the flies’ initial postural state. Furthermore, flies plan a takeoff direction even in instances when they choose not to jump. This sophisticated motor program is evidence for a form of rapid, visually mediated motor planning in a genetically accessible model organism.

⏳ 5 min

Q2: Interpret the difference between a “simple feed-forward motor program” and “motor planning”.

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

The fly’s stereotyped escape response to a visual stimulus is mediated by the hard-wired giant fiber neural pathway (ie. the properties of the neural circuit is genetically encoded).

In voluntary flight take-off, early wing elevation leads to a stable take-off. During escape take-off, unlike voluntary flight take-offs, the wings are pulled down close to the body. The fly translates faster but also rotates rapidly about all three of its body axes, resulting in tumbling flights.

Therefore, the two types of Drosophila flight initiation result in different flight performances once the fly is airborne, and that these performances are distinguished by a trade-off between speed and stability (ie. evidence for constraints on the evolution of these two behaviors… ideally they would both be speedy and stable).

Fig. 101 A) Voluntary flight take-offs. B) Escape flight take-offs (triggered by a looming disk). From Card and Dickinson (2008) Performance trade-offs in the flight initiation of Drosophila.¶

Giant Fibers¶

“Giant Fibers” are neurons with large axon diameter. They are ubiquitous across the animal kingdom in escape neural circuits. Voltage “spikes” travel faster from one place to another in neurons with larger diameter axons. When a message of “get out of here” needs to rapidly get from a sensory input to a motor output, the larger the axon diameter, the faster the message can activate the muscle activation pattern.

Mauthner Cell: C-Start Escapes¶

Evolution (Selective Pressure and Adaptation)¶

The following video shows a successful Mauthner-mediated escape of a zebrafish from a demselfly nymph (from Hecker et al (2020)1.

The following video shows an unsuccessful (too slow) Mauthner-mediated escape in a zebrafish without the Mauthner cell:

Absence of the Mauthner neurons significantly reduced the likelihood of escaping the predatory strikes of damselfly nymphs compared with the simultaneously present control larvae1.

Neural mechanisms¶

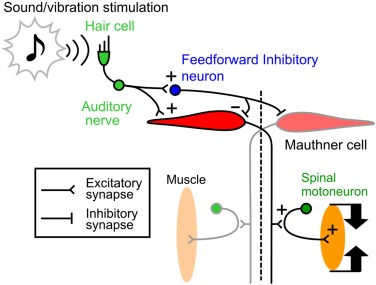

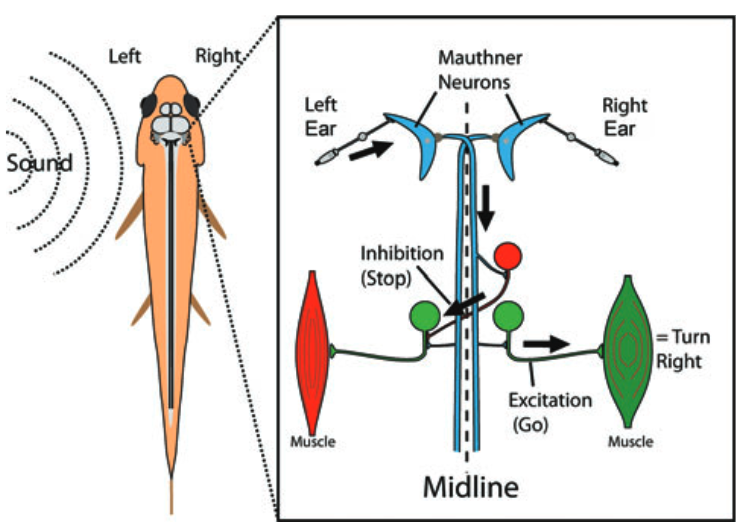

The first step of the Mauthner-mediated c-start escape is a c-shaped bend away from the source of the threatening stimulus. The escape neural circuit (especially for the initial c-shape bend) has been extensively studied. A simplified diagram of the basic circuit is shown in Figure 99.

Fig. 102 The Mauthner cell escape circuit (From Catania 20112). An auditory cue arriving on the left side of the fish generates an action potential in the left Mauthner neuron that travels down the axon to the opposite side of thetrunk where motor neurons are excited on the right side. At the same time, a crossed inhibitory neuron inhibits the musculatureon the left side, allowing for a bend (C-start) to the right and away from the stimulus.¶

Mauthner cells are the largest diameter neurons in the vertebrate spinal cord. They originate in the hindbrain and project down the spinal column.

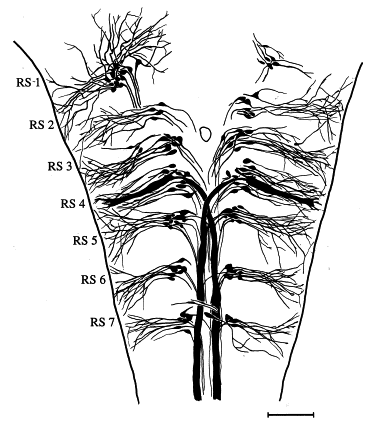

Fig. 103 View of the dorsal brainstem of the goldfish. Anterior is to the top. The illustration is a reconstruction of reticulospinal neurons in seven segments, or rhombomeres (RS 1–RS 7). The Mauthner cell is the thickest one (the largest diameter). Processes extending from the somas to the periphery are primarily lateral dendrites; all the cells have axons that course to or across the midline, and extend into the spinal cord. Scale bar, 200 μm. (From Lee et al., 1993a.)¶

Phylogeny (Evolutionary History)¶

Mauthner cells first appear in lampreys (being absent in hagfish and lancelets), and are present in virtually all teleost fish, as well as in amphibians (including postmetamorphic frogs and toads). Some fish, such as lumpsuckers, seem to have lost the Mauthner cells however3

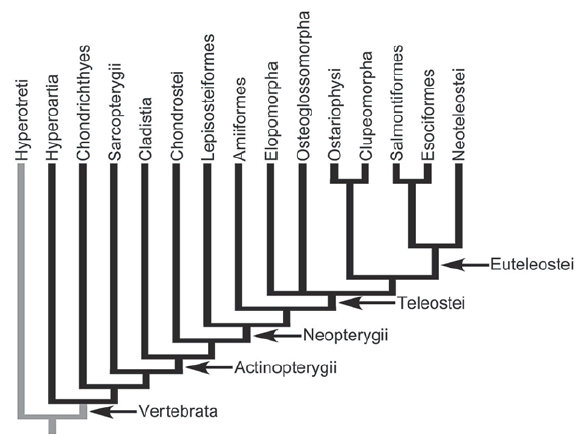

Fig. 104 Mapping of chordate phylogeny4. Black branches denote groups in which Mauthner cells have been reported in at least some species or developmental stages. Mauthner cells have not been observed in Hyperotreti (hagfish) shown in gray.3 Sarcopterygii contains tetrapods, and therefore mammals.¶

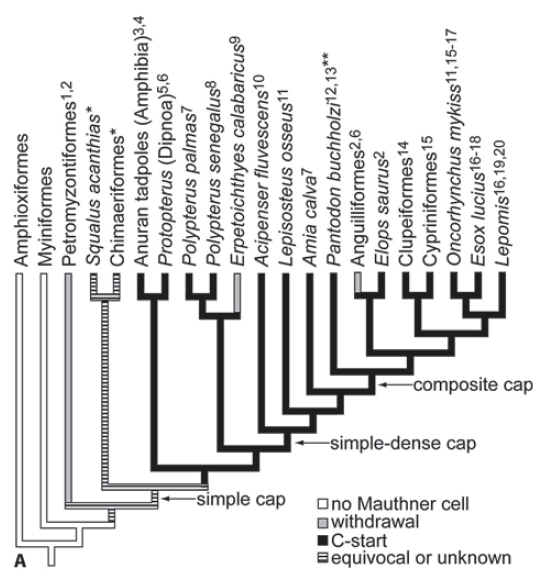

Fig. 105 Evolution of escape behavior in the context of axon cap morphology among basal actinopterigian fishes. Arrows point to transitions in axon cap morphology. C-start behavior is common among aquatic osteichthyans (sarcopterygians and actinopterygians). Withdrawal behavior seems to have arisen multiple times within the vertebrates. In withdrawal, both sides of the body contract in unison rather than out of phase with each other.

In the case of the Chimaeriformes, a pectoral fin driven startle has been suggested [Bone et al., 1977] and S. acanthias performs a C-start-like behavior [Domenici et al., 2004] that is likely not M-cell elicited. The double asterisk denotes that the C-start behavior of this animal is vertical.3¶

THe comparison of morphological and behavioral phylogenetic patterns which Hale et al3 describe, provide a first step toward understanding how evolutionary mechanisms have shaped the neural mechanisms of escape behavior.

⏳ 10 min

Q3: How would the circuitry need to differ for a withdrawal escape that is mediated by the Mauthner cells?

Development¶

Q4: What kinds of developmental explanations/questions do you have about c-start escape behavior in fish?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Escape FAP code-breaking by the tentacled snake¶

The following high-speed video taken by Kenneth Catania shows how the tentacled snake uses a body fake to trick fish into fleeing toward the snake’s head. The video also shows how the snake aims its strike to a location where it expects the fish’s head to be instead of tracking its movement.

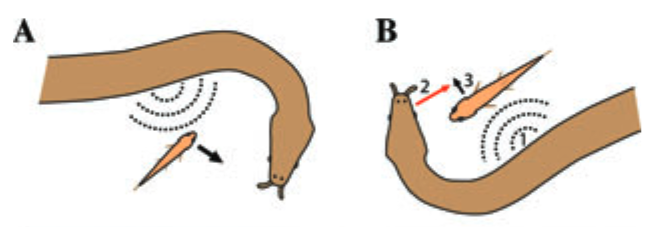

Fig. 106 (From Catania 20112) (A) A tentacledsnake startles a fish toward its subsequent strike. (B) When fish approach the snake at a right angle to the long axis of the jaws, fish cannot be startled toward the strike. Instead, snakes startle fish in a predictable direction and bias their subsequent strike to the future position of the fish’s head.¶

Q5: Think about how the tentacled snake would affect the evolutionary explanations for the stereotyped c-start escape. What are the selective pressures on the behavior and what are their sign?

Non-rapid escape behaviors¶

Stereotyped actions such as aimless jumping and running do not allow escape in all situations.

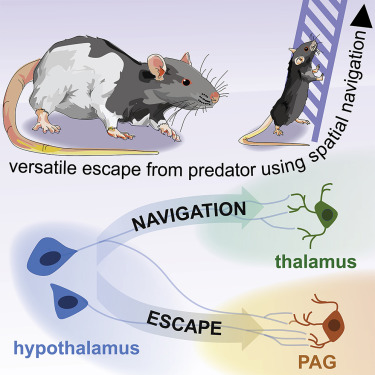

In many animals, escape behavior is context-specific and requires rapid evaluation of local geometry to identify and use efficient escape routes. For example, escaping a burning building requires rapid evaluation of the architecture to locate and use the most direct route to safety.

The the dorsal premammillary nucleus (PMd) of the hypothalamus is a candidate brain region for mediating these types of escapes. Its two main outputs are 1) the dorsolateral periaquiductal gray (dlPAG; which is known to provide command signals for escape behavior such as jumping and fast running) and 2) a navigation- and memory-related structure called the anteromedial ventral thalamic nucleus (amv). The amv contains neurons that encode heading direction (like the central complex of insects).

Wang et al (2021) found that the PMd only recruits its thalamic targets when it performs escapes requiring navigation5. The following video shows that experimental stimulation of PMd neurons elicites escape from a novel and geometrically complex environment even with no prior training or familiarization. Optogenetic activation of other nuclei implicated in escape, such as the anterior and ventromedial hypothalamus elicited stereotyped hyperlocomotion and jumping, but mice do not escape the room.5

Additional Resources¶

Neural mechanisms of startle behavior Eaton, Robert C. New York : Plenum Press; ©1984. Available , Stacks (2nd Floor) ; QP372.6 .N48 1984

Wang Yu, et al (2020) Flexible motor sequence generation during stereotyped escape responses. eLife 2020;9:e56942

Basic neural circuits for locomotion

- 1(1,2)

- 2(1,2)

- 3(1,2,3,4)

Hale ME (October 2000). “Startle responses of fish without Mauthner neurons: escape behavior of the lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus)”. Biol. Bull. 199 (2): 180–2.

- 4

Based on Hurley et al. [2007] and Løvtrup [1977], but see Janvier [2007] for a discussion of phylogenetic relationships of early vertebrates

- 5(1,2)