Sexual Selection

Contents

Sexual Selection¶

Why?

Evolution by natural selection is often summarized as evolution by “survival of the fittest.” How is it, then, that in certain species of spiders (also in certain insects) the male is eaten by the female in the act of copulation?

The existance of behaviors that reduce an individual’s survival are striking.

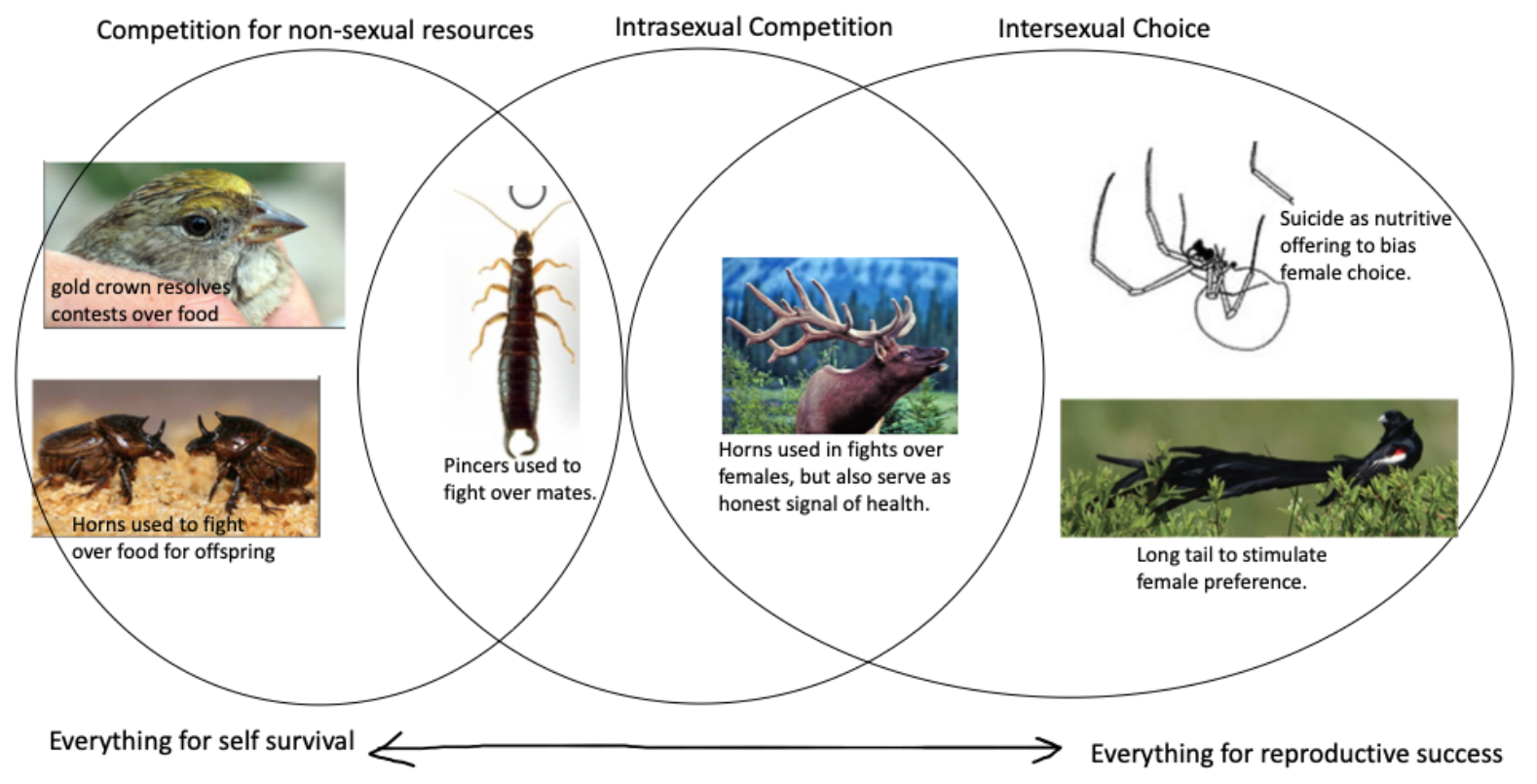

The range of factors that can exert selective pressure on behavior is vast. Some behaviors are shaped more by individual survival and physiological fitness, others are shaped more by reproductive success. Behaviors shaped by reproductive success directly (for example, behaviors that function in mate choice) tend to result in elaborate traits that actually detract from survival (like health or predation risk).

Sexual Dimorphism¶

In many species, sexually-selected behaviors or behavioral elaborations have evolved only in one sex and not both: di: two; morph: form. When different phenotypes are distinguished by sex, it is called dimorphism.

Several key reproductive concepts are key to understanding sexual dimorphism…

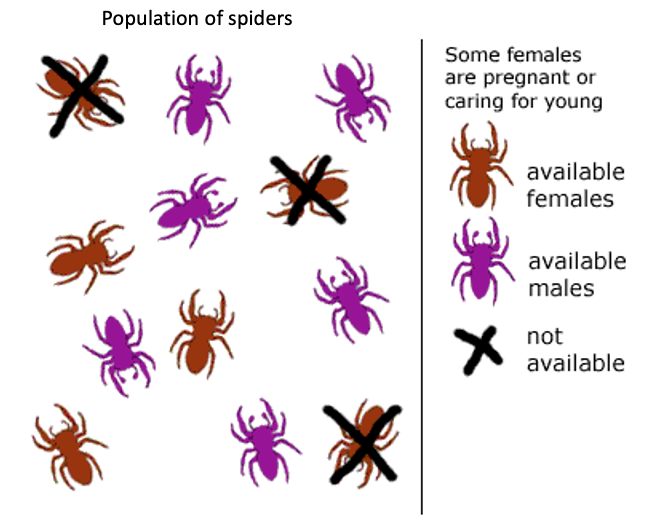

- sex ratio¶

ratio of males to females

- operational sex ratio ¶

ratio of sexually receptive males to sexually receptive females

- reproductive variance¶

the variance in mating success across individuals of one sex

⏳ 5 min

Q1: What is the sex ratio of this spider population compared to its operational sex ratio?

Q2: Assuming that each individual can only mate once each season, which sex will have a more difficult time finding a mate?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Ideally, an animal would want to choose a mate that would provide it with the most reproductive fitness (number, viability, and mating success of offspring). Inequality in the ability to be choosy about a mate is one of the main factors leading to sexually dimorphic behavior. Ultimately, it is better to mate with someone than no one. If you are a member of the sex that exists in abundance (according to the operational sex ratio), then the most pressing issue you face is just to secure a mate at all. If you are a member of the sex that exists in scarcity, then you are basically guaranteed someone to mate with, and the more pressing issue you face is making sure you get the best mate possible. Reproductive variance within a sex can mimic the effects of a skewed operational sex ratio (and/or compound it).

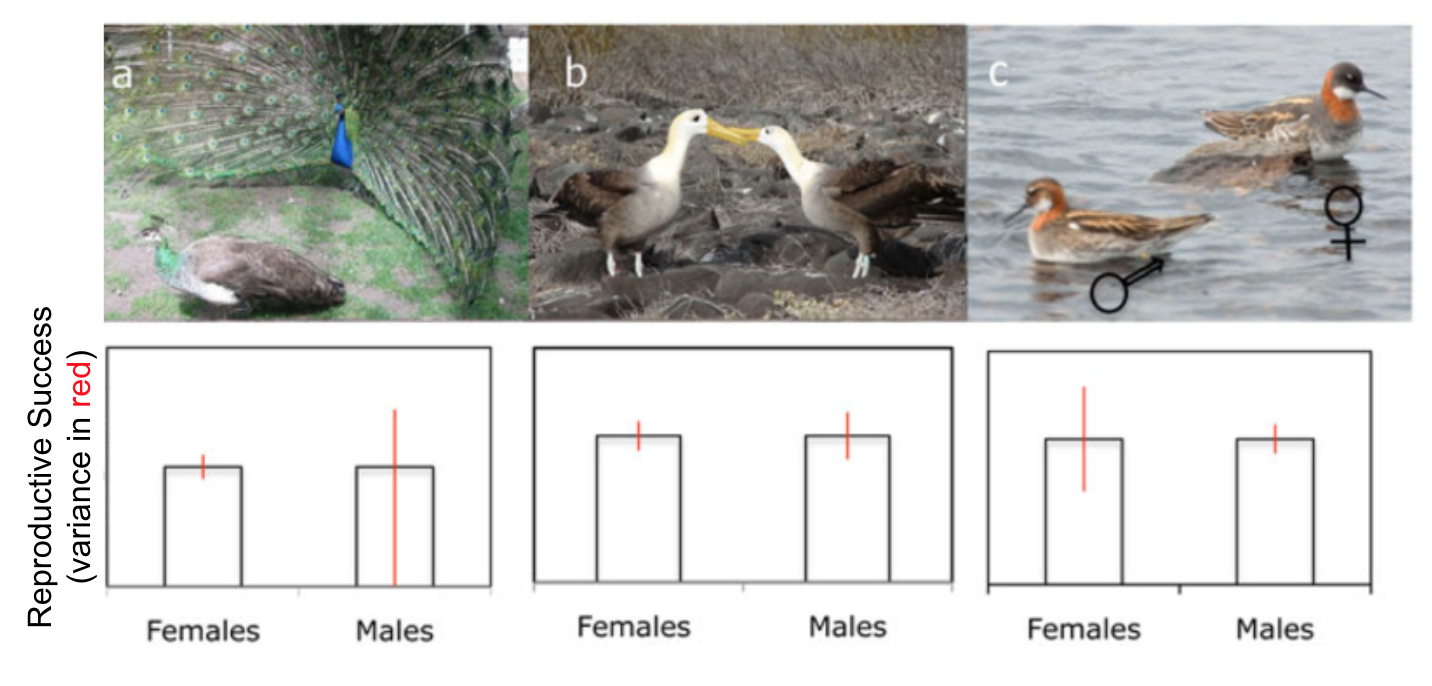

In animals with an operational sex ratio close to one and equal reproductive variance between the sexes, both sexes likely face similar mate procurement struggles. In these animals, the need to attract mates is equal for both sexes and we predict that there will not be sexual dimorphism.

Fig. 138 Black swans exhibit mutual ornamentation. Both males and females look the same, with curled wing feathers that serve a sexual function. These feathers are used in mutual mate choice, where both males and females have a preference for mates with wing feathers that are more curled.¶

Many factors weigh in on mate choice to shape behavior over evolutionary timescales. Mating competition is one category. And there are three main categories related to mate choice: direct benefits, indirect benefits, and exploitation.

Direct Competition¶

Intra-sexual contests over mates or mating territory can lead to sexually dimorphic elaboration of weaponry. Animals develop traits that help them win reproductive rights over others of the same sex.

Remember that not all contests necessarily result in direct fighting to physically determine a winner. These weapons can primarily signal the ability to win a fight, and rarely be implemented in actual fighting (ie. dancing fiddler crabs).

Direct Benefits¶

Mates are selected based on what they can offer directly to the chooser that will increase its physiological fitness.

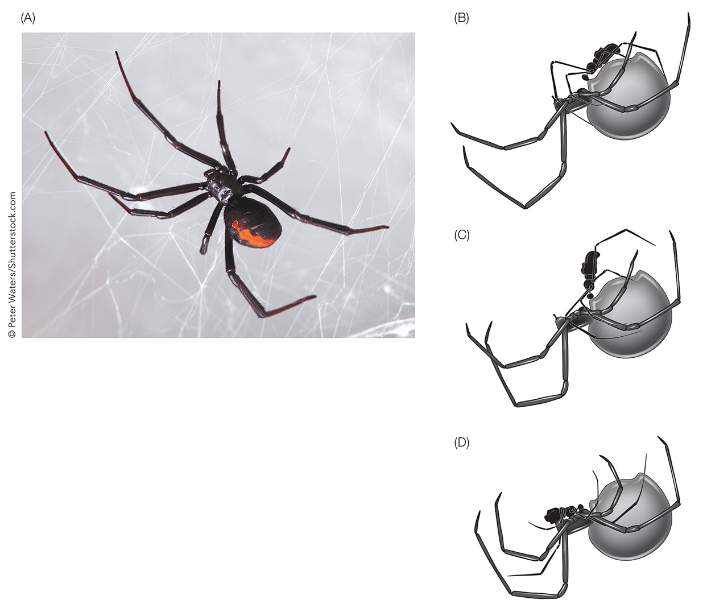

For example, male redback spiders self-sacrifice for the female after mating. First, the male transfers its sperm transfer organ into to the female spider. The organ then performs the sperm transfer on its own. Now lacking its reproductive organ, the male spider voluntarily performs a flipping handstand to land itself into the jaws of the female. The female eats the male while the sperm transfer takes place.

Fig. 139 Sexual suicide and cannibalism in the redback spikder.¶

Indirect Benefits¶

Mates are selected based on what they can offer indirectly to the chooser’s offspring.

Good Genes¶

The trait provides a way for individuals to judge each other’s quality.

Handicap¶

Reproductive benefit from choosing mates based on how costly a behavior/trait is to the individual’s survival. Only the individuals with the best genes would be able to survive having a phenotype that is costly to its ability to survive. Lower quality individuals would not be able to incur the cost if they are to survive.

For example, in peacocks, the cumbersome tail might signal biological strength if the peacock manages to survive despite the size of its tail. The idea was proposed by Israeli biologists Amotz and Avishag Zahavi.

Fig. 140 The male peacock elegantly displays its tail to the female (top), but is awkward and combersome in locomotion (bottom).¶

Indicator¶

Reproductive benefit from choosing mates based on “conditionally expressed” behavior/traits–the behavioral phenotype is correlated with the physiological condition of the animal.

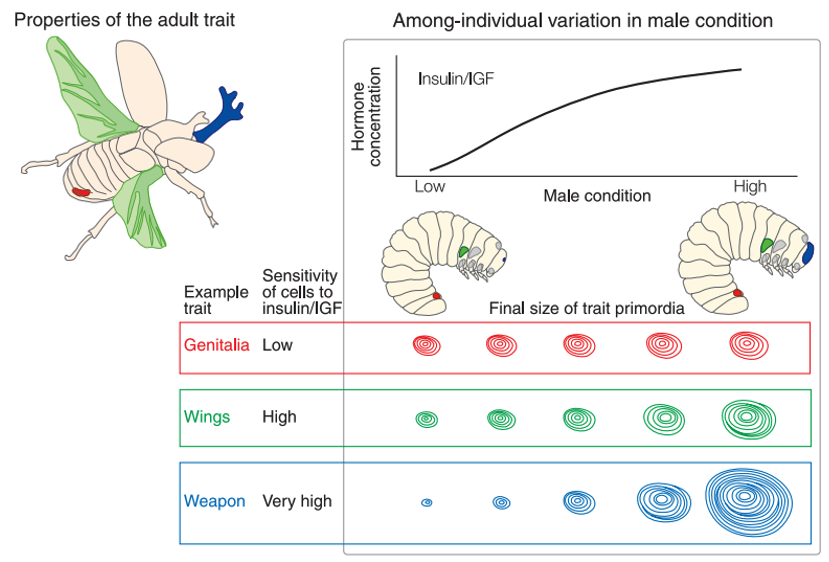

Individual nutritional state and physiological condition are reflected in circulating concentrations of insulin-like peptides and Insulin Growth Factors (IGFs). IGFs modulate the rate of growth of individual trait primordia. However, some traits are more sensitive than insulin that others. An increase in the sensitivity of cells within a particular trait would lead to disproportionately rapid growth of that trait in the largest, best-condition individuals (i.e., exaggerated trait size) and smaller trait sizes in low-condition individuals.

Fig. 141 Proposed mechanism for the evolution of trait exaggeration through increased cellular sensitivity to insulin/IGF signaling. Image from Emlen et al (2012)1.¶

Individuals with better survival fitness could be distinguished by the size of morphological traits. These traits would be intrinsically reliable signals of fitness due to the proximate mechanim regulating their growth.

If mating with long-horned males provided the female’s offspring with these high-quality genes, then we would predict the offspring would have better survival fitness than offspring of short-horned males.

Attractiveness¶

(aka Runaway Selection)

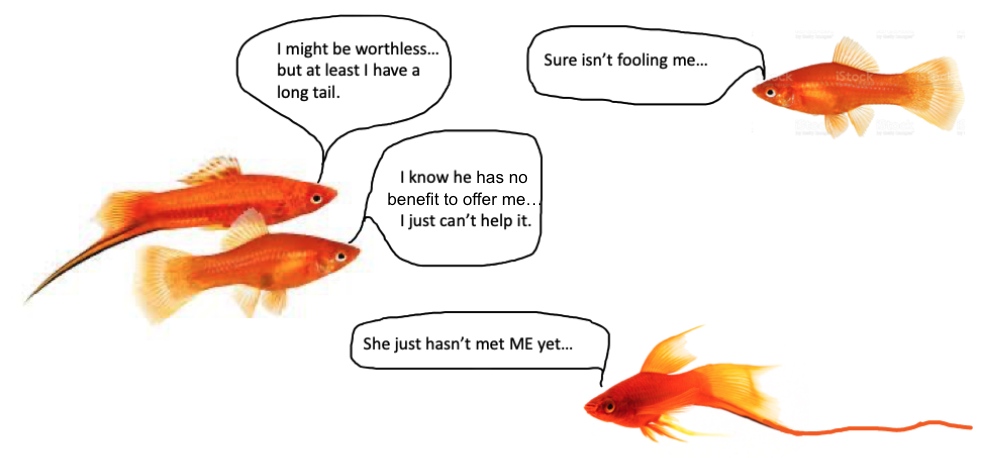

The offspring will be more reproductively successful themselves simply because they are more attractive to females. In this case, the sexually selected phenotype might not have anything to do with how well it is able to survive, but rather how many mates it can get.

During the breeding season, widowbird males moult into black plumage with orange and white shoulders, or epaulettes, and grow extremely long tails – up to half a metre (20 inches) long. Their long tails make flying difficult, which interferes with fighting ability in territory defense an makes them more vulnerable to predators.

Likely, these traits started out as indicators of fitness (ie good genes), but then elaborated beyond the point where they served individual fitness.

⏳ 5 min

Testing the role of these factors in mate selection.

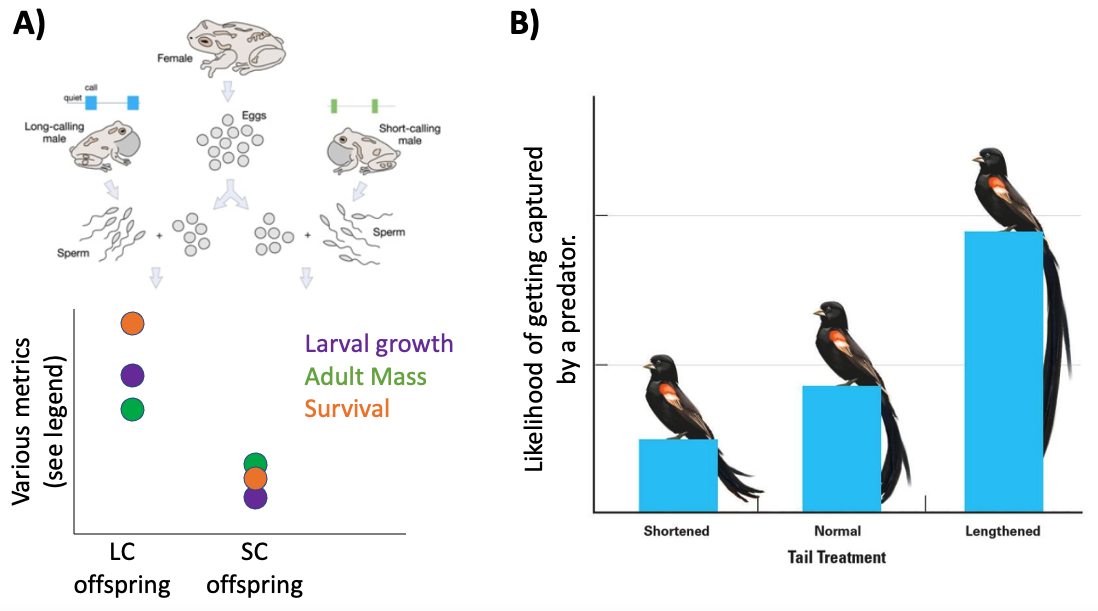

Fig. 142 A) In frogs, females are more attracted to males with long advertisement calls (LC) versus short advertisement calls (SC). Using in-vitro fertilization, researchers fertilized female eggs with sperm from either LC males or SC males. The quality of offspring from LC and SC sperm were then tested by metrics of fitness (growth, survival, etc).

B) In widowbirds, females are attracted to males with elaborately long tail feathers. Researchers artifically altered the length of male tail feathers (shortening or elongating them) and tested the likelihood that the males in each conditoin would be captured by a predator.¶

Q3: For each of these experiments/results, which sexual selection hypothesis does it test: Handicap (good genes), Indicator (good genes), or Attractiveness? Why?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Exploitation¶

(aka Chase-away Selection)

Sexual selection for traits that tap into pre-existing sensory biases.

⏳ 5 min

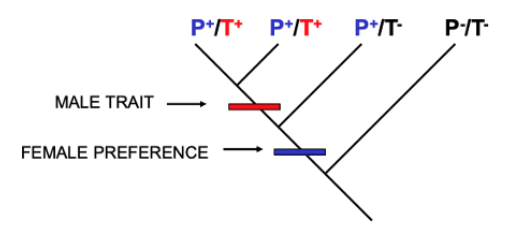

Fig. 143 A phylogeny of female preference for a male behavior (P; blue) and the male behavior itself (T; red). The phenotype of extant species is indicated by P/T and +/-. Ancestors in which each of the phenotypes first evolved are indicated along the phylogeny.¶

Q4: If you were investigating whether a sexually dimorphic behavior could be explained by “exploitation” or “attractiveness,” which of the two conclusions would the results of this phylogenetic analysis support and why?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Cryptic choice¶

Bias in fertilization that occurs after mating or in the release of gamets… either manipulating fertilization of gametes directly, or or through development via manipulation of fetal growth or survival.

The ability of Drosophila females to eject sperm after mating. Also seen in many bird species such as dunnocks. This biases fertilization of their eggs for certain mating partners.

In some bird species, the female adjusts the amount of testosterone that she contributes to a fertilized egg in relation to the attractiveness of her mate.