Neural Mechanisms

Contents

Neural Mechanisms¶

Day 1; Responses template if needed

Day 2; Responses template if needed

Making Connections to the Past and Moving Forward¶

Introductory discussion based on Podcast.

FAPs

Sequencing

Hydraulic Pressure Model

“Activation” (sign stimulus implied)

“Circuits” versus brain areas

Emotional state, “motivation”, and behavior

The Building Blocks¶

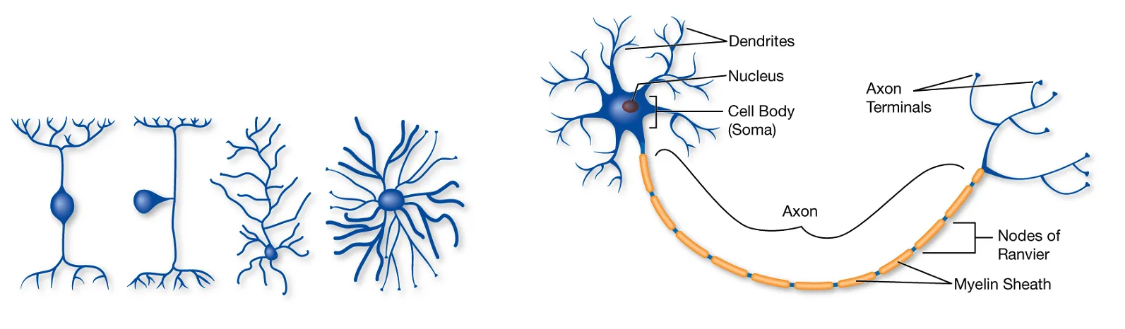

Cell types: neurons¶

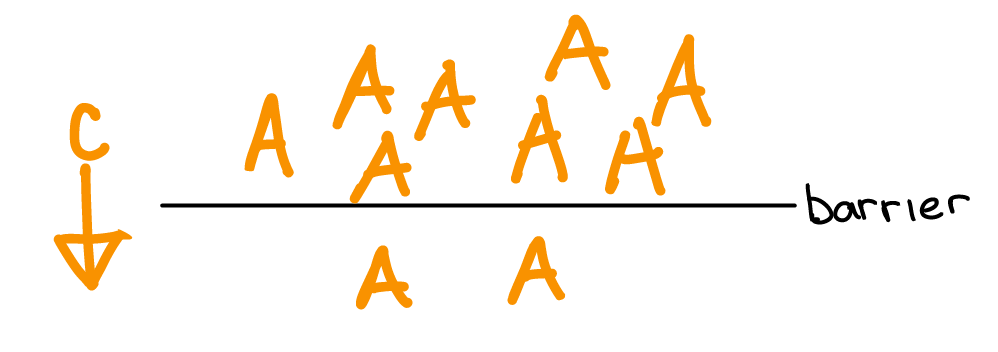

Fig. 17 Basic neuron anatomy. Neuron morphology is diverse (left), but follows a basic template of ‘parts’: axon, dendrite, cell body (right). Importantly, like other cells, neurons are enclosed by a barrier that controls permeability and movement of solutes across it.¶

Electrochemical Forces¶

The electrochemical force forms the basis of how the nervous system causes behavior. Changes in membrane voltage are used to compute and transmit information throughout the nervous system.

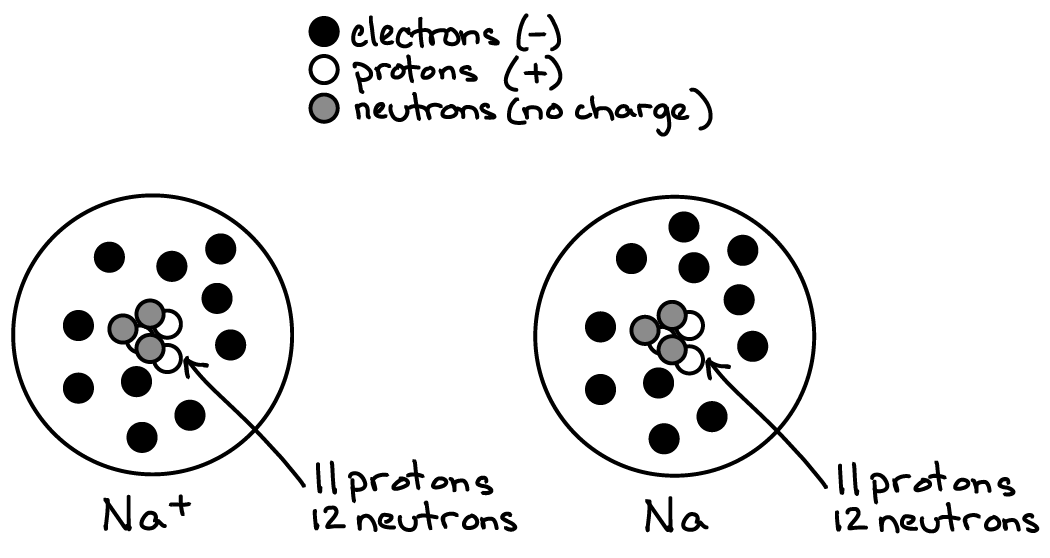

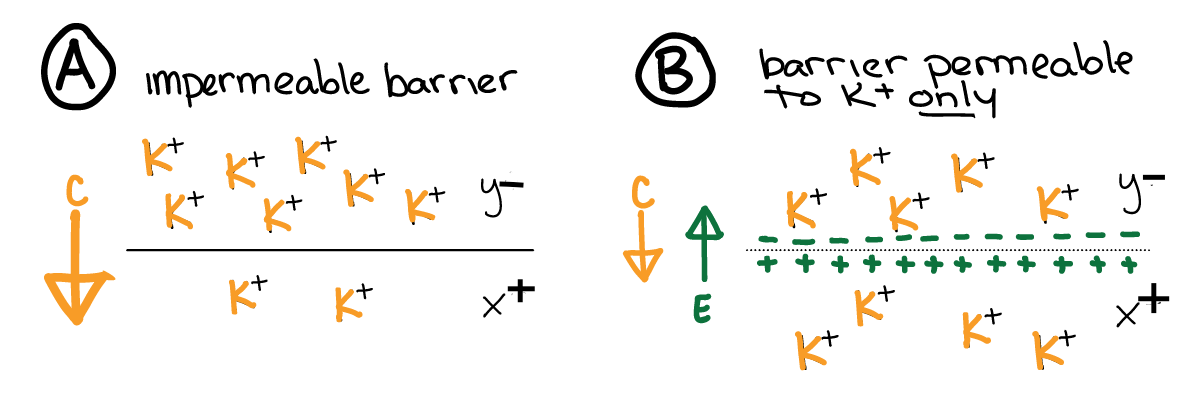

Differences in atom concentration across a barrier result in a chemical force on atoms directed from areas of high concentration to low.

If the barrier gets a hole in it, then the atoms will move due to the chemical force.

If the atoms are charged (ie. ions), then an electric gradient will accumulate as the ions move in response to the chemical force. The electric gradient generates an electric force that builds up until the opposing chemical and electrical forces equal each other. The electrical force that balances the chemical force is called the equilibrium potential for that ion.

Fig. 18 The electrical force (\(e\), green arrow) opposes the chemical force (\(c\), yellow arrow) for an ion. When a membrane becomes permeable to an ion with a concentration force (A to B), the electrical force increases until it exactly opposes the (now reduced) chemical gradient (B). The result is a stable and measurable voltage (potential) across the membrane.¶

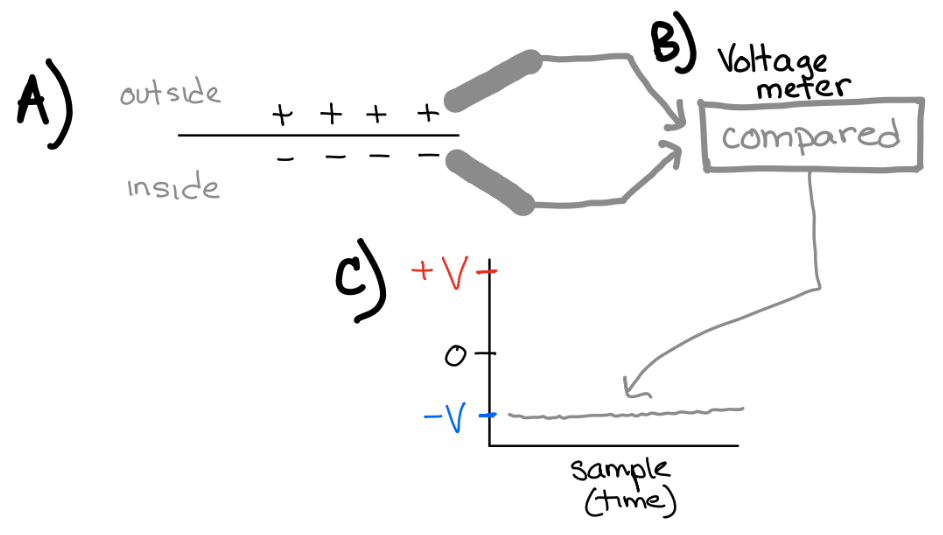

We measure the membrane potential of a neuron using a voltage meter. Neurons have a “resting” membrane potential (in the absence of any synaptic input). However, there are mechanisms for changing a neuron’s relative conductance (permeability) of ions (which we will get to in a bit).

Fig. 19 A) neurons have a resting membrane potential. B) Voltage meters can measure the membrane potential. The voltage inside is referenced to the voltage outside. C) The resting membrane potential of neurons is usually negative inside relative to outside.¶

Neuron membrane potential¶

In neurons, different ions have different concentration gradients across the membrane (and different charge). Therefore, the equilibrium potential for different ions is different.

⏳ 5 min

Consider the following table of values for K+, Na+, and Cl- across a neuron’s membrane. From these concentrations, we can use a specific equation (Nernst equation) to calculate the membrane potential at which the electrical force opposes the chemical force on the ion1. We call this membrane potential the equilibrium potential for the ion.

ion |

internal |

external |

Equilibrium |

|---|---|---|---|

Na+ |

15 |

145 |

+61 |

K+ |

150 |

4 |

-97 |

Cl- |

10 |

110 |

-64 |

Consider the following table of relative ion permeability (“conductance”, \(g\)) across a neuron’s membrane and the total difference in electrical potential across that membrane.

\(g_{Na+}\) |

\(g_{K+}\) |

\(g_{Cl-}\) |

membrane potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

0.2 |

0.8 |

0 |

0.2*(+61) + 0.8*(-97) = -65.4 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1*(-64) = -64 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0 |

0.8*(+61) + 0.2*(-97) = +29 |

Q1: If the membrane is only permeable to K+ ions, what would be the voltage across the cell’s membrane (ie. the membrane potential)?

Q2: How can you change the membrane potential of a neuron?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

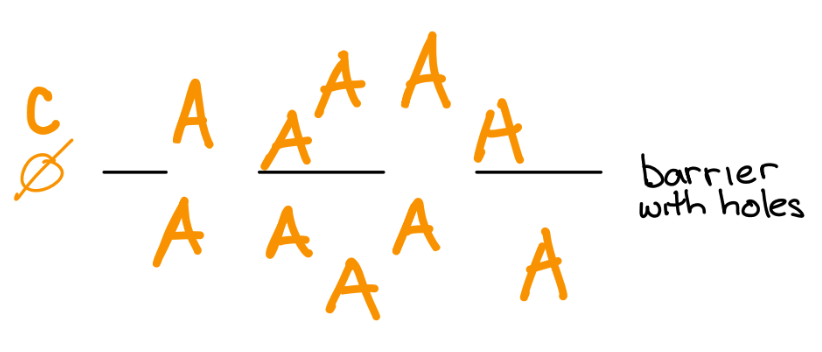

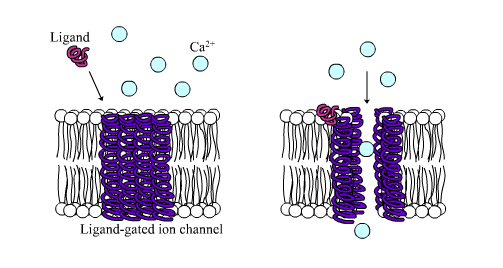

Membrane permeability is controlled by special proteins in the membrane called ion channels. Different ion channels are specific for the permeability of different ions. Also, different ion channels have different criteria for being “open” (ie. increasing the conductance for their ion).

Some ion channels always let their ion through.

Some ion channels are gated by voltage and only let their ion through when the membrane potential is above or below certain voltage levels.

Some ion channels are gated by the binding of molecules or proteins to their surface.

⏳ 5 min

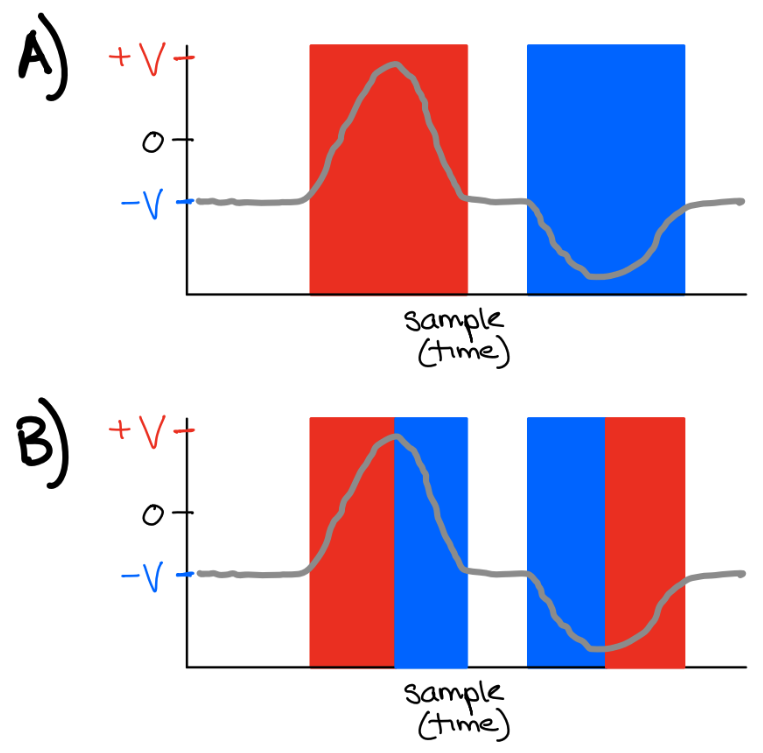

Examine the plots of membrane potential (V) aross time in Figure 21 and the terminology used to describe the changes in membrane potential.

Fig. 21 Grey: membrane potential (voltage)

A) Red: depolarized. Blue: hyperpolarized.

B) Red: depolarizing. Blue: hyperpolarizing.¶

Q3: How would you define ‘depolarized’?

Q4: How would you define ‘depolarizing’?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

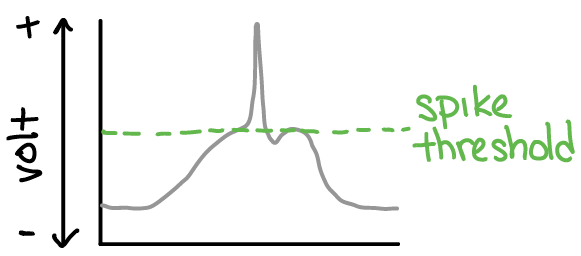

A neuron is activated when it is depolarized above it’s spike threshold (and therefore generates a spike). Spikes are a special type of “non-linear” voltage event. They are special because they cause “synaptic events” (see next section). As a general heuristic, keep in mind that more membrane depolarization leads to more spikes.

Fig. 22 Plot of membrane potential (y-axis) across time (x-axis; left-to-right). The membrane potential starts at “rest”, then depolarizes, then depolarizes so much that it reaches spike threshold (green dotted line), and a voltage spike is generated. This voltage spike would then go on to cause a synaptic event (see next section).¶

Systems and Circuits and Behavior¶

Synapses¶

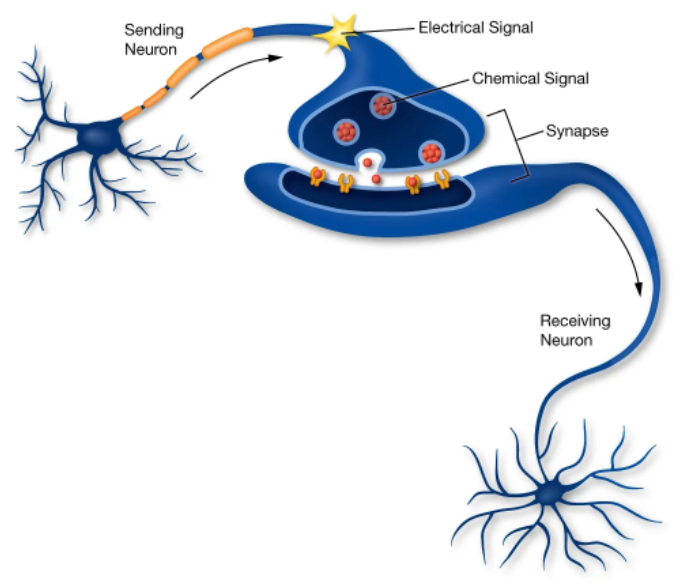

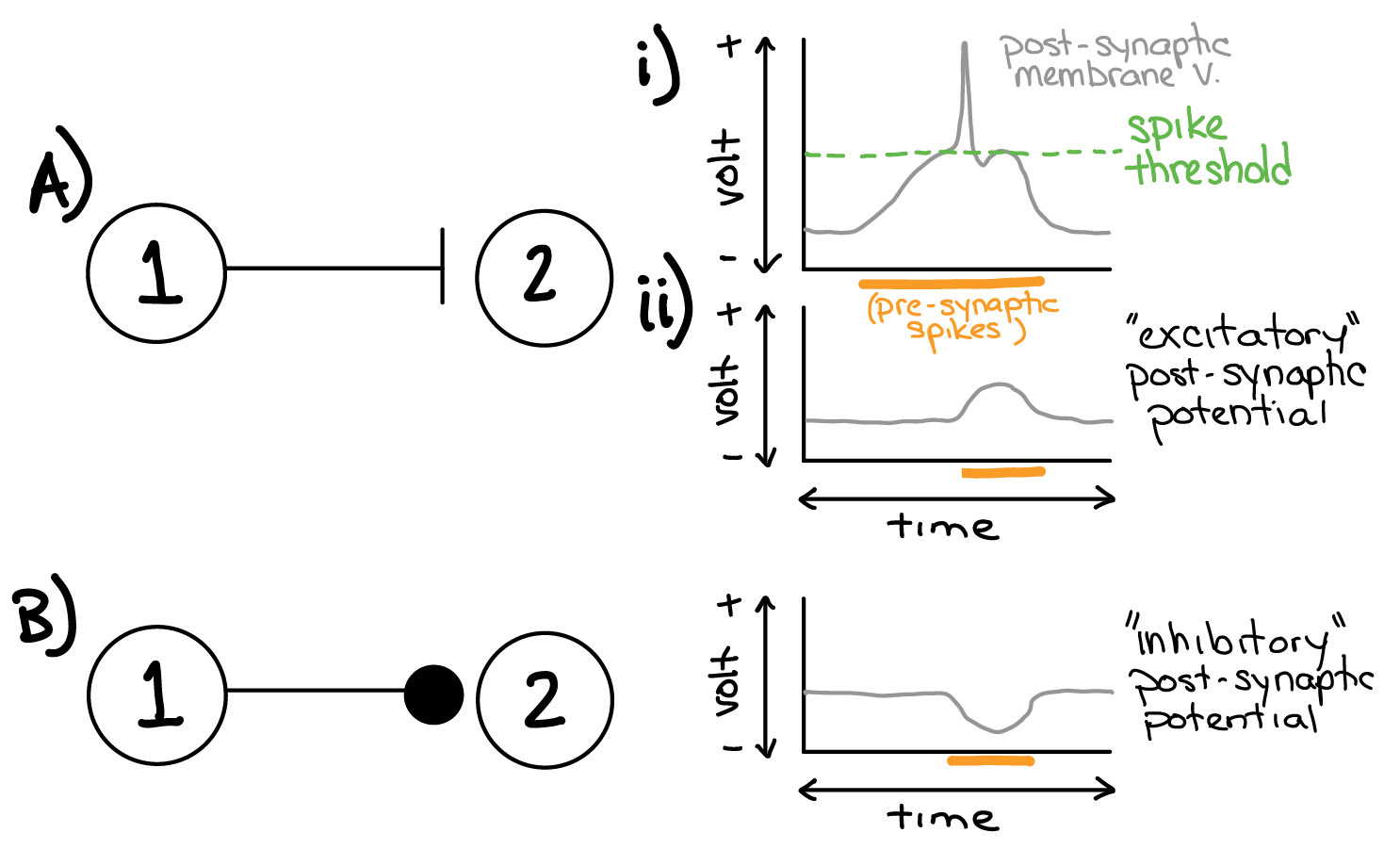

Neurons effect each other via synapses. There are neurons before (pre-synaptic) and neurons after (post-synaptic) synapses. Specifically:

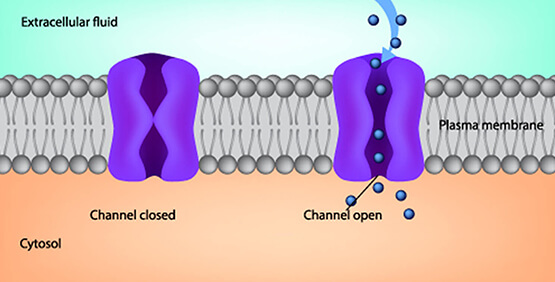

Voltage spikes in a “pre”-synaptic neuron cause the release of molecules (neurotransmitters and/or neuromodulators). Different types of neurons have different neurotransmitters.

Synaptic events change ion permeability in a “post”-synaptic neuron. Receptors (membrane proteins) are permeable only to specific ions and only when they bind specific molecules. Different types of neurons have different receptors.

Fig. 23 Synapses between neurons transform electrical events into chemical events and back to electrical events. Chemical signals are released by the pre-synaptic neuron membrane when a voltage spike (“electrical signal”; large depolarization) occurs. These bind to ion channels on the post-synaptic membrane. When the ion channels bind the chemical signal, they open and let their ion through the membrane (increasing its conductance).¶

Fig. 24 An example cartoon of a ligand-gated calcium ion channel3. When the ligand (a molecule) binds to the receptor (the ion channel), it then lets its ions through.¶

For a neurotransmitter to change ion permeability of a neuron, the neuron must have receptors for the neurotransmitter. Two broad types of neurotransmitter-receptor pairs are excitatory and inhibitory.

⏳ 15 min

Fig. 25 Example synaptic connectivity (left; ball and stick diagrams) and the result on post-synaptic membrane potential (right; gray) for: A) Excitatory synaptic connection and B) Inhibitory synaptic connection. Ai) Depolarization above a specific value (green; spike threshold) causes a brief voltage spike event. Orange bar denotes time during which the pre-synaptic neuron is spiking (ie. the synapse is activated).¶

Consider the K+, Na+, and Cl- equilibrium potentials established in table 1 and 2 (shown in the margin to the right).

Q5: Let neuron #2 have a “resting” K+ to Na+ conductance ratio of 0.9 to 0.1, and no Cl- conductance. What would be the “resting” membrane potential of neuron #2?

Q6: To produce the result shown in Ai and Aii (excitatory post-synaptic potential in response to pre-synaptic spikes), would you predict that neuron #2 had neurotransmitter receptors that were permeable to K+, Na+, or Cl-? Why?

Q7: To produce the result shown in B, would you predict that neuron #2 had neurotransmitter receptors that were permeable to K+, Na+, or Cl-? Why?

Q8: What would happen to the membrane potential of neuron #2 if it did not have any receptors that could detect the neurotransmitter released by neuron #1?

⏹️ STOP here for today

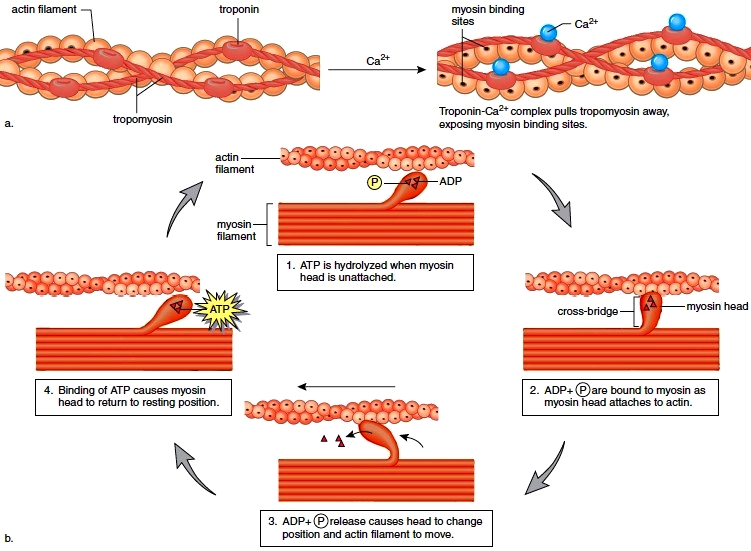

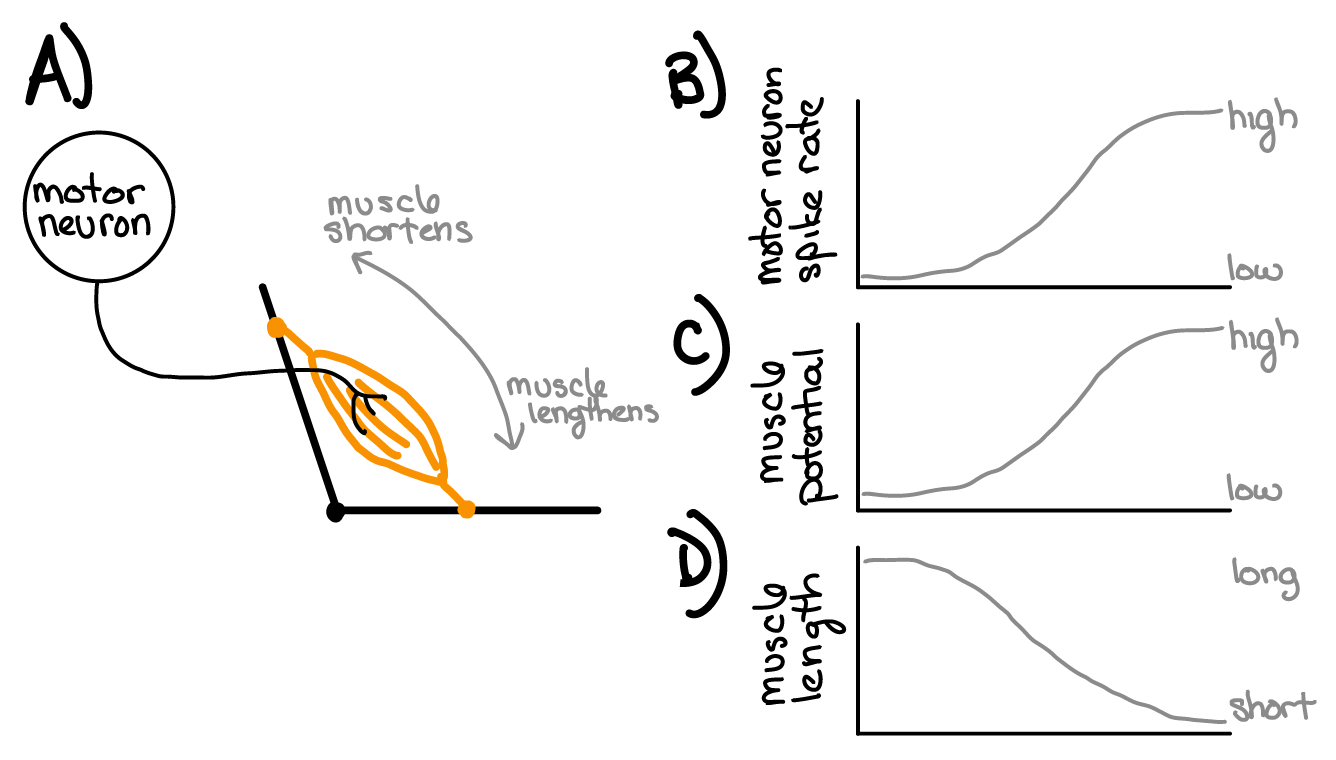

Muscles¶

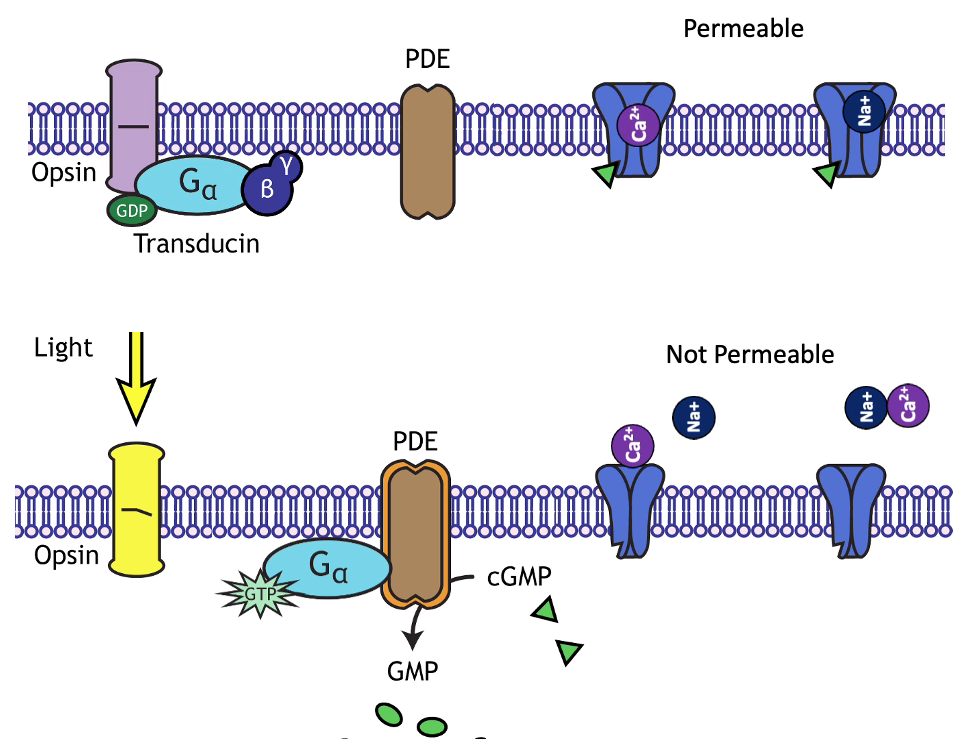

Muscles are specialized “excitable” cells that contract (shorten) when their membrane becomes depolarized (because depolarization opens voltage-gated Calcium channels… see margin). Muscle shortening (and lengthening) is the foundation of all movement, and therefore of behavior.

Muscle depolarization is controlled synaptically by motor neurons – the special class of neurons that synapse onto muscle cells.

The relationships among motor neuron spike rate, muscle membrane potential, and muscle length are summarized in Figure 26.4

Fig. 26 A) Motor neurons synapse onto muscles. B) Motor neurons vary their rate (frequency) of spike events. C) Muscle cell membrane potential depolarizes in response to motor neuron spike events. More spikes = more depolarization D) Muscle cells decrease in length when they are depolarized.¶

Sensors¶

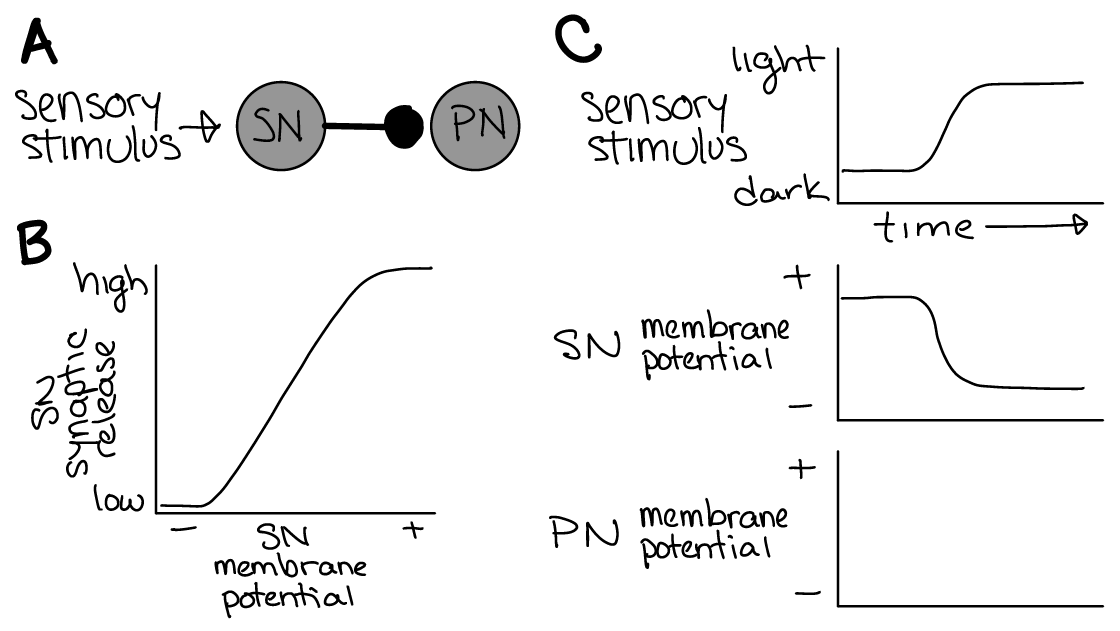

Sensors are special types of neurons whose membrane potential is under the control of physical energy/stimuli in the environment. In other words, sensors transform physical stimulus energy/information into electrical energy/information. Different sensors are specialized for light, pressure, odor, etc.

Let’s consider a sensor that hyperpolarizes in response to an increase in light (example mechanism in the margin image) and depolarizes in response to an decrease in light. The hyperpolarization decreases its release of molecules (neurotransmitters) at its synapses. Let’s say this sensor neuron (SN) provides inhibitory synaptic input to a “post-synaptic” (PN) neuron (Figure 27A).

Fig. 27 A) A sensor neuron (SN) that hyperpolarizes in response to light synapses onto a post-synaptic neuron (PN). The synapse is inhibitory for the PN.

B) Synaptic neurotransmitter release from the sensor is proportional to its membrane potential.

C) Example changes in membrane potential for the SN and PN in response to a change in the light stimulus over time.¶

⏳ 3 min

Q1: What happens to the membrane potential of the post-synaptic neuron (PN, Figure 27C) when more light shines on the sensor (ie. the sensory stimulus goes from dark to light)?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Circuits¶

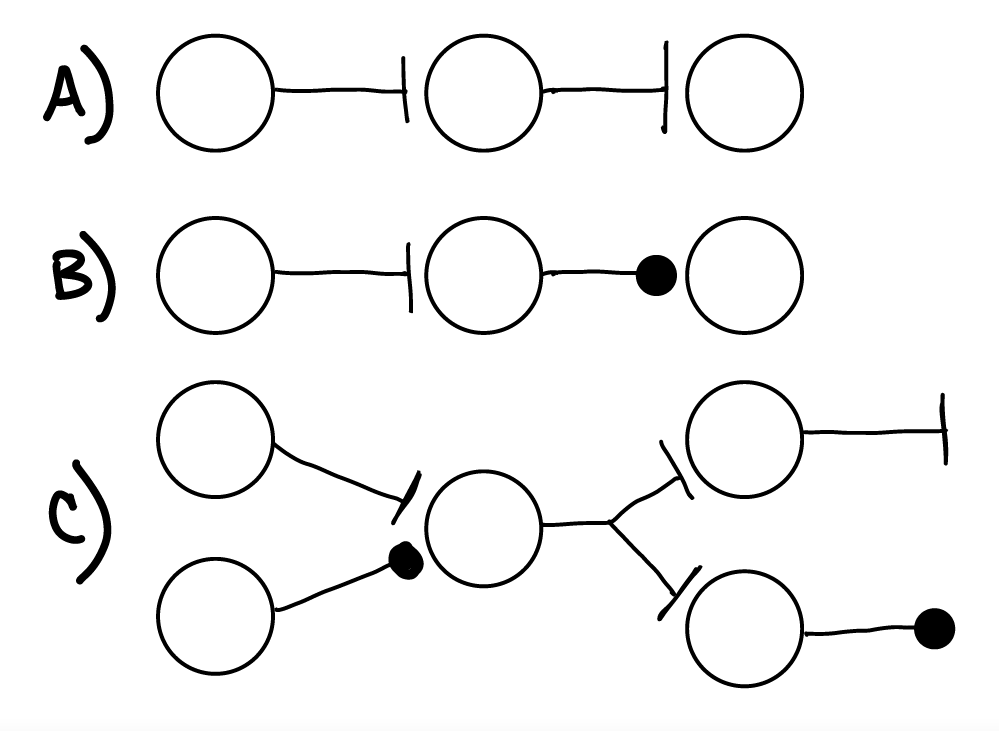

When groups of neurons connect with each other via inhibitory or excitatory synapses to form circuits, complex outputs can emerge. Later today, we will examine a specific example of this phenomenon: Central Pattern Generator (CPG) circuits.

Fig. 28 A) Two excitatory synapses in a row. If the first neuron depolarized and spiked, the second neuron would then depolarize soon after and may spike as well. If the first neuron hyperpolarized, it would not spike and the second neuron would just stay at its resting membrane potential (no change in its output).

B) An excitatory synapse followed by an inhibitory synapse. If the first neuron depolarized and spiked, the second neuron would then hyperpolarize soon after.

C) Examples of convergence and divergence in heterogeneous neural circuits.¶

⏳ 5 min

Q2: Draw a neural circuit (composed of an auditory sensor neuron, a motor neuron, and a muscle) that contracts a muscle when the sound amplitude in the environment increases. Use a sensor neuron that is depolarized by increased sound amplitude (remember that depolarization increases its voltage spike activity).

Q3: Draw a neural circuit composed of the same three neurons as in Q2. But now, make the circuit contract the muscle when the sound amplitude in the environment decreases. Hint: you can make any neuron have a “resting” membrane potential above spike threshold (so that it is spiking in the absense of synaptic input).

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Behavior¶

Neuroscience seeks to understand how neural circuits orchestrate behavior. In general, this involves examining all of the following processes:

Sensors must respond to stimuli that contain information about the world.

Neurons must use that information and compute with it.

Computations lead to decisions about what actions are needed in response.

Internal factors can also influence action selection.

Neurons then orchestrate actions by dynamically coordinating sets of muscles.

Case Study: Cricket Acoustic Communication¶

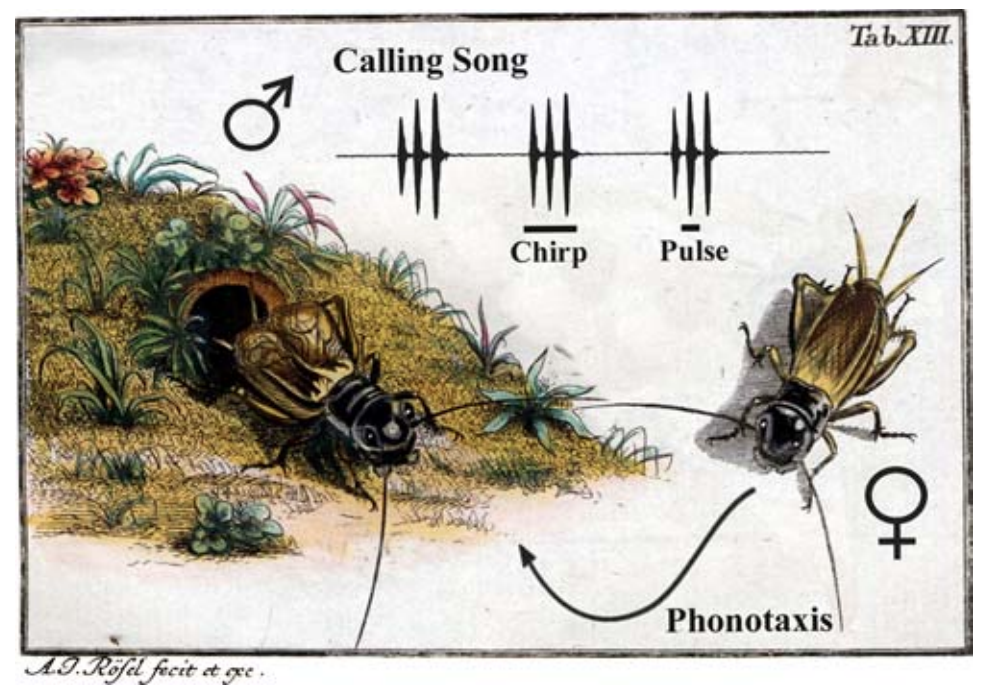

Fig. 29 Acoustic behavior of Gryllus campestris5. A male sings in front of its burrow by rubbing the elevated front wings together. The calling song consists of single sound pulses (syllables) grouped into chirps. This behavior is stereotypically patterned across time. Females attracted by the calling song perform phonotaxis and walks towards the singing male using acoustic cues for orientation. This behavior involves walking and orienting (navigating).¶

Command versus Pattern¶

Stereotyped motor patterns (for example, FAPs) are orchestrated by neural circuits that coordinate the contraction/relaxation among sets of muscles. These circuits are activated by a command signal (after a decision has been made to do the action). But, remarkably, the command signal itself (the spiking output of a command neuron) does not need to be patterned. This feature of motor control can be demonstrated by using experimental techniques enabling control over the spiking activity of “command neurons”.

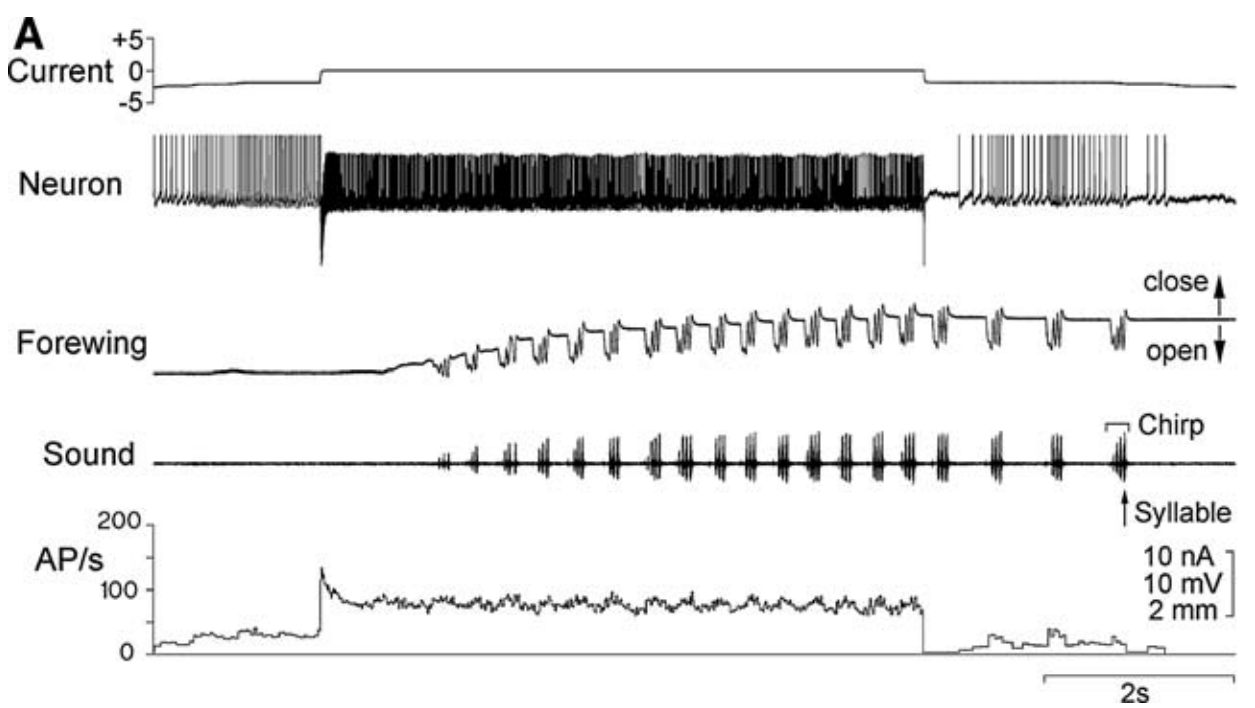

Fig. 30 The motor control of calling song5. Neuron: A recording of the command neuron’s membrane potential across time in the brain of Gryllus bimaculatus. Current: A current applied across the membrane of the command neuron via a wire placed inside the neuron. Increasing the neuron’s voltage spiking (AP/s) elicits the generation of “calling song” (Sound) because it causes forewing movement (Forewing: the cricket closes its wings and starts to “sing” by moving the wings back and forth against each other).¶

The command neuron (“Neuron” in Figure 30) causes the cricket to sing, but its activity is unpatterned. What causes the patterning of the movement required to produce the patterned song?

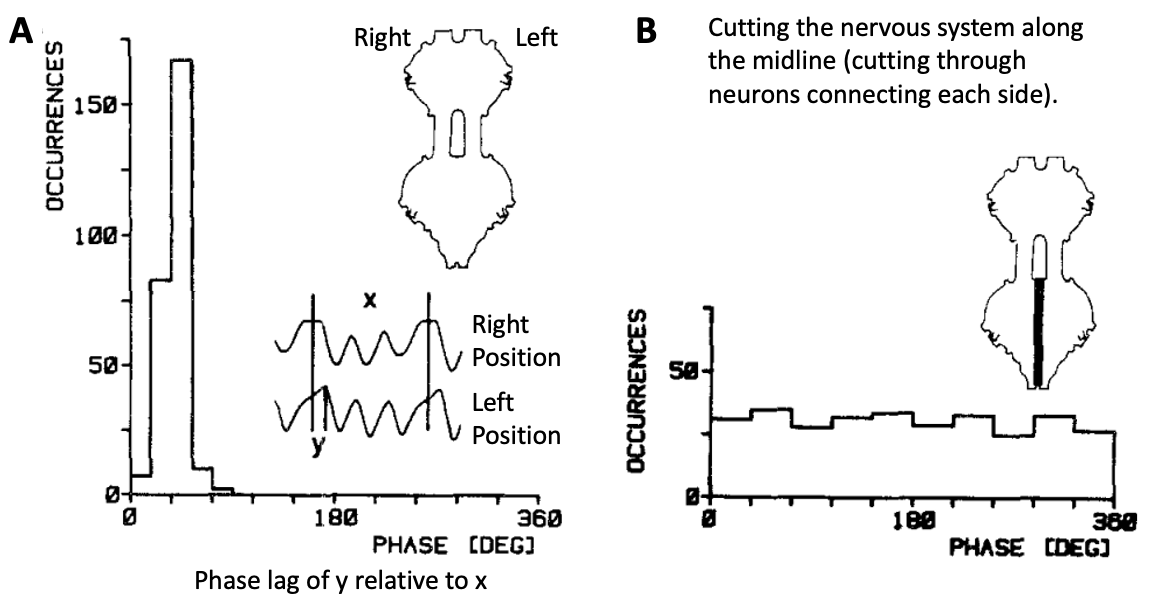

- central pattern generator (CPG)¶

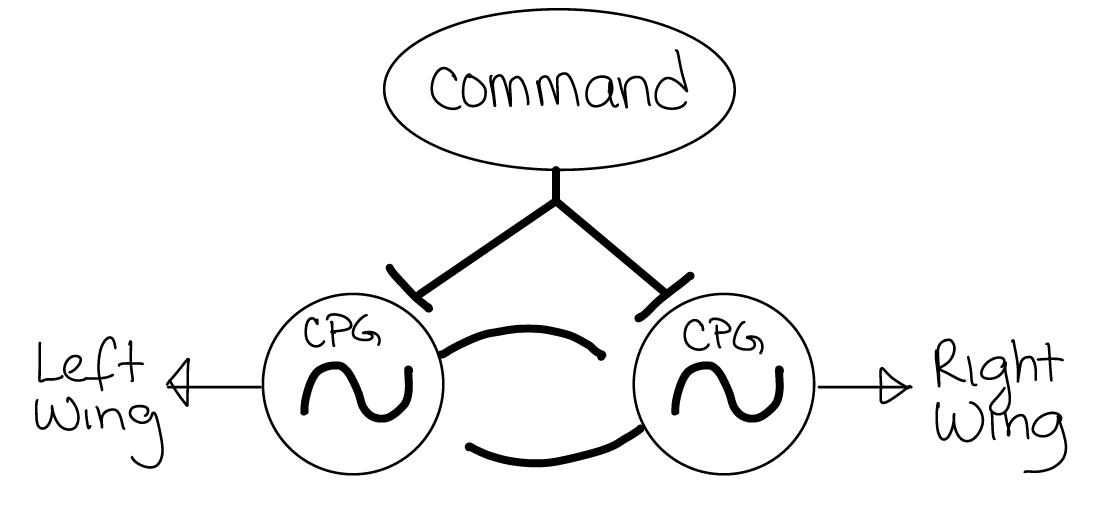

A neural circuit that can produce patterned output in the absence of patterned input. In other words, it is a circuit that (once activated) is self-sufficient at producing a stereotyped pattern of spikes that regularly changes over time.

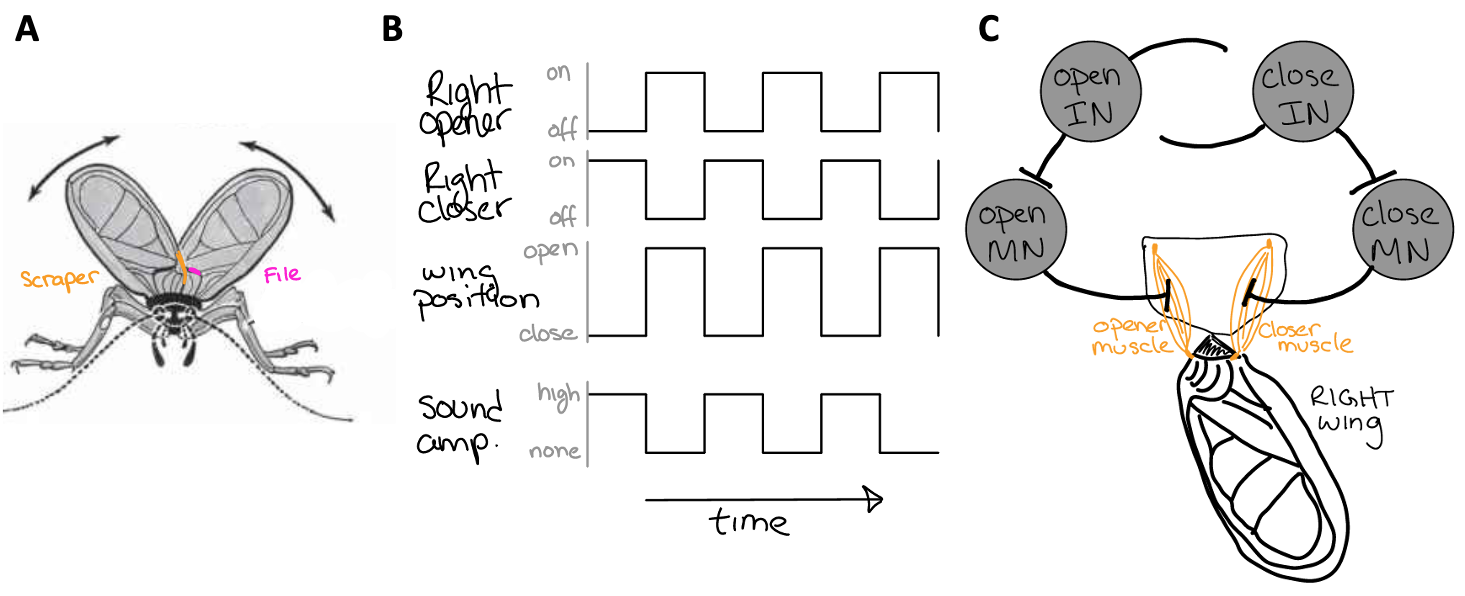

Fig. 31 The anatomy of a chirp.

A) The cricket’s wings have a file and a scraper. When the cricket closes both of its wings together, the scraper rubs the file and vibrates the wings, producing sound.

B) The pattern of activity among wing opener and closer muscles, wing position (open and closed), and sound.

C) A central pattern generator for wing movement that is comprised of motor neurons (MN) (that synapse on wing opener and closer muscles) and interneurons (IN) (that synapse on MNs and each other). The INs provide excitatory synaptic input to MNs. MNs provide excitatory synaptic input to muscles (thus contracting them). INs are also provide synaptic input to each other.¶

⏳ 5-10 min

Q4: The synaptic input from each IN to the other was left undefined in Figure 31C. Do these need to be excitatory or inhibitory synapses? Why?

Usually, multiple CPGs need to be coordinated with each other to generate even simple behavioral actions.

Fig. 32 Entire CPG circuits (like the one in Figure 31) are often represented by a circle with a tilde symbol. In this example, there is a wing CPG on each side of the cricket’s body that controls the open/close movement of each wing. When the command neuron is activated, it excites both CPG circuits with unpatterned input.¶

Q5: The CPGs for wing movement on each side of the cricket’s body need to be correctly coordinated with each other to generate song – the wings need to close toward each other at the same time. To achieve this action, what type of synaptic connection (inhibitory or excitatory) is needed from each CPG to the other?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Sensory Filtering¶

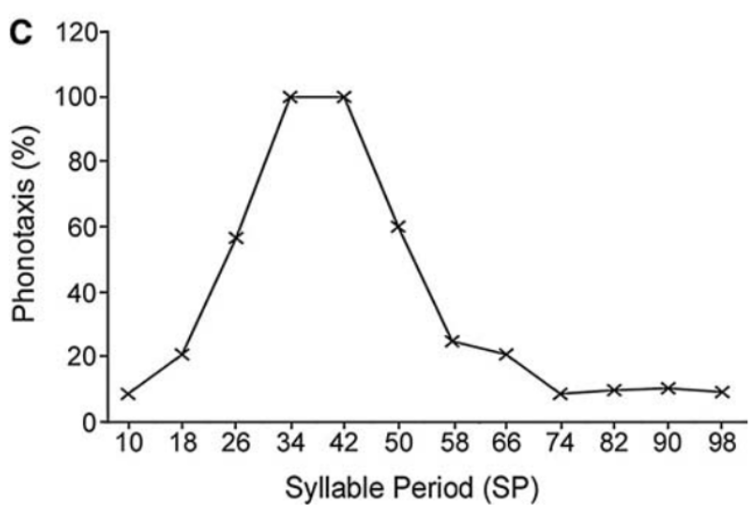

Not all sensory stimuli are the same. Stimuli have lots of different features. In the case of cricket song, we will consider two features: the syllable period (SP) and the loudness (amplitude). Both of these features can vary across a wide range.

SP is generally specific to different species (different species generate song with distinct SP). However, amplitude tends to vary across individuals (or time) more than between species. Amplitude can also vary due to environmental features such as distance from the sound source.

Sensory filtering refers to the specificity of sensors across stimulus features.

Different sensors respond to different modalities of information (ie light, sound, odor).

Within each modality, different sensors respond best to specific features of a stimulus (ie frequency of sound, wavelength of light).

Stimulus features themselves can then vary along a continuum. Sensors are often specific to just a small range of feature values (500 nanometer light, 200 Hz sound) within a given stimulus modality or category.

Without sensory filtering, there would be no specificity in behavioral responses to stimuli.

For example, female crickets move toward male cricket song when they hear it. We call this phonotaxis and it is an FAP. It would be maladaptive for female crickets to phonotax in response to all sound. Therefore, there are sensory filters in the female cricket nervous system that are more sensitive to the song of a male cricket than to anything else. In addition, these sensory filters are most sensitive to the species-specific SP of conspecific male song.

So what does sensitive to mean? We will examine this in the next set of figures and questions.

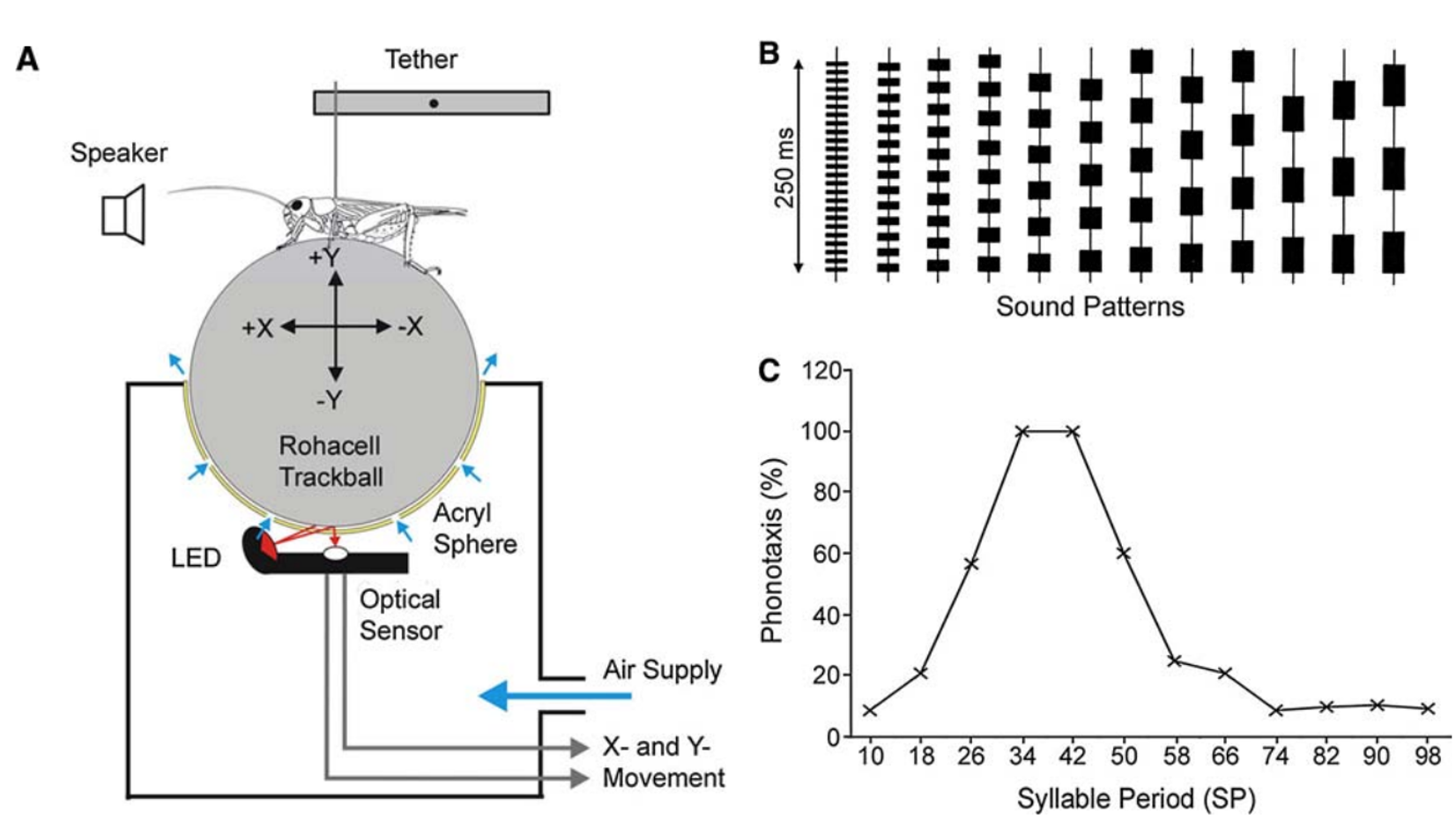

Fig. 33 Sensory filtering for species-specific song5.

A) Trackball system for analysing cricket phonotaxis. See also this video of the behavior

B) Sound patterns to test sensory tuning for conspecific song.

C) Tuning curve of phonotaxis demonstrates the strongest response to SP34–SP42, which corresponds to the natural range of SP. Phonotaxis declined at shorter or longer syllable periods.¶

How does the mechanism of sensory filtering explain this kind of behavioral specificity?

At a basic level, let’s think about a simple neural mechanism for FAPs:

Sensory stimuli are transformed into changes in neuron membrane potential by sensors (the set of sensors comprise the sensory filter).

The sensory filter synapses onto decision centers in the brain, which contain (or synapse onto) “command neurons” for specific FAPs.

Command neuron activation (depolarization above spike threshold) drives the activity of coordinated CPGs that actually cause the muscle activation pattern over time for the specific FAP.

The flow of information is: sensory stimuli –> sensory filter –> decision –> FAP.

Therefore, we can infer a lot about sensory filters in the nervous system by examining behavioral responses. Additionally, we can observe how the stimulus threshold for behavior is related to the stimulus threshold for spiking in neurons.

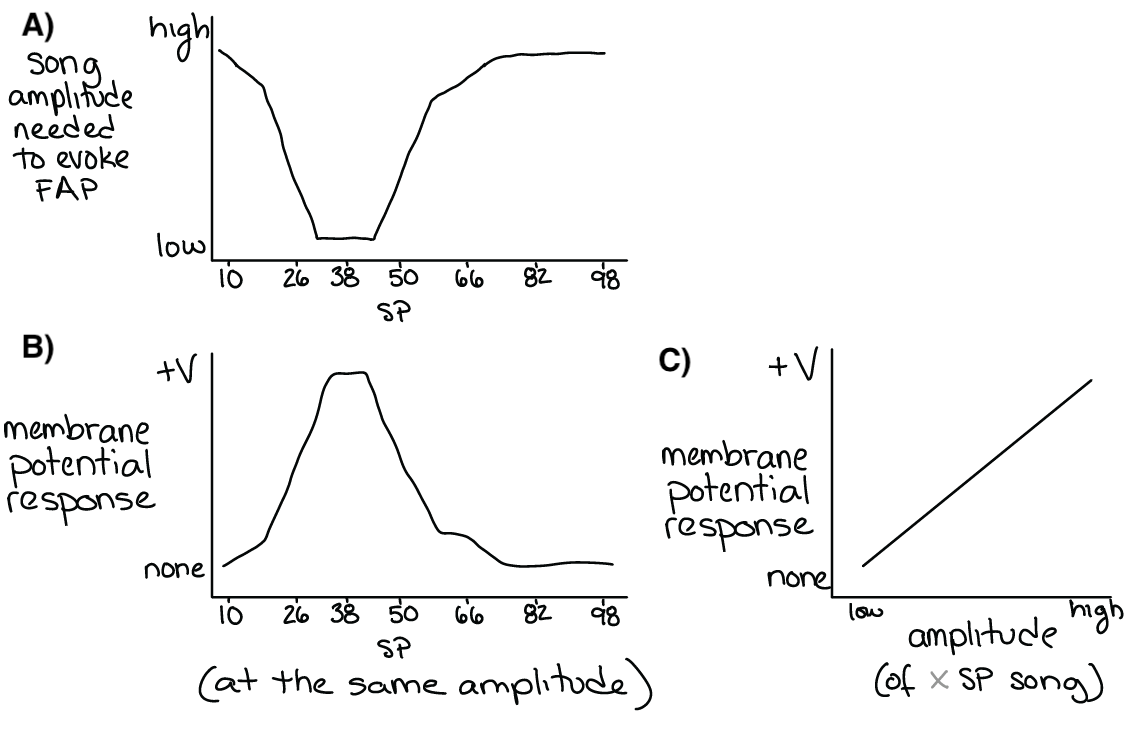

Fig. 34 A) The song amplitude needed to evoke phonotaxis behavior (the inverse of the Figure 33C – see margin).

B&C) Both the amplitude and the SP of song effect the membrane potential of a sensory filter. Above a certain membrane potential, the sensory filter neuron(s) will spike and activate post-synaptic (downstream) decision-making or command neurons.¶

⏳ 5 min

Q6: The song amplitude needed to depolarize the sensory filter neurons above spiking threshold is most closely related to the:

a. stimulus threshold in Lorenz’s model

b. behavioral threshold in Lorenz’s model

c. the action specific potential in Lorenz’s model

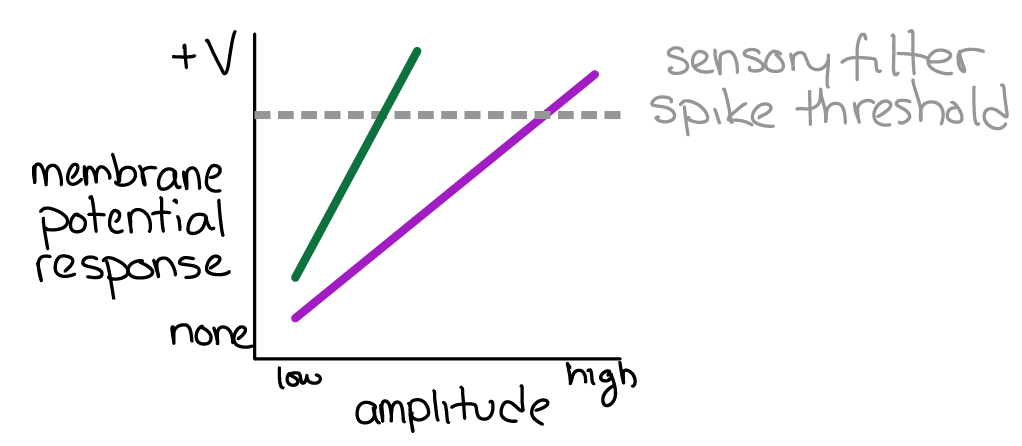

Q7: The data shown in Fig 35 are from an experiment measuring the membrane potential of sensory filter neurons during the presentation of song stimuli. Songs with two different SP values were tested (38 and 60 SP). Which color corresponds to 38 SP and which color corresponds to 60 SP?

Fig. 35 The membrane potential response (y-axis) to stimuli of different amplitudes (x-axis) and SP values (color). If the sensory filter spike threshold is reached, the downstream command neuron is activated and an FAP is produced.¶

⏹️ STOP here for today

Central Pattern Generators… continued¶

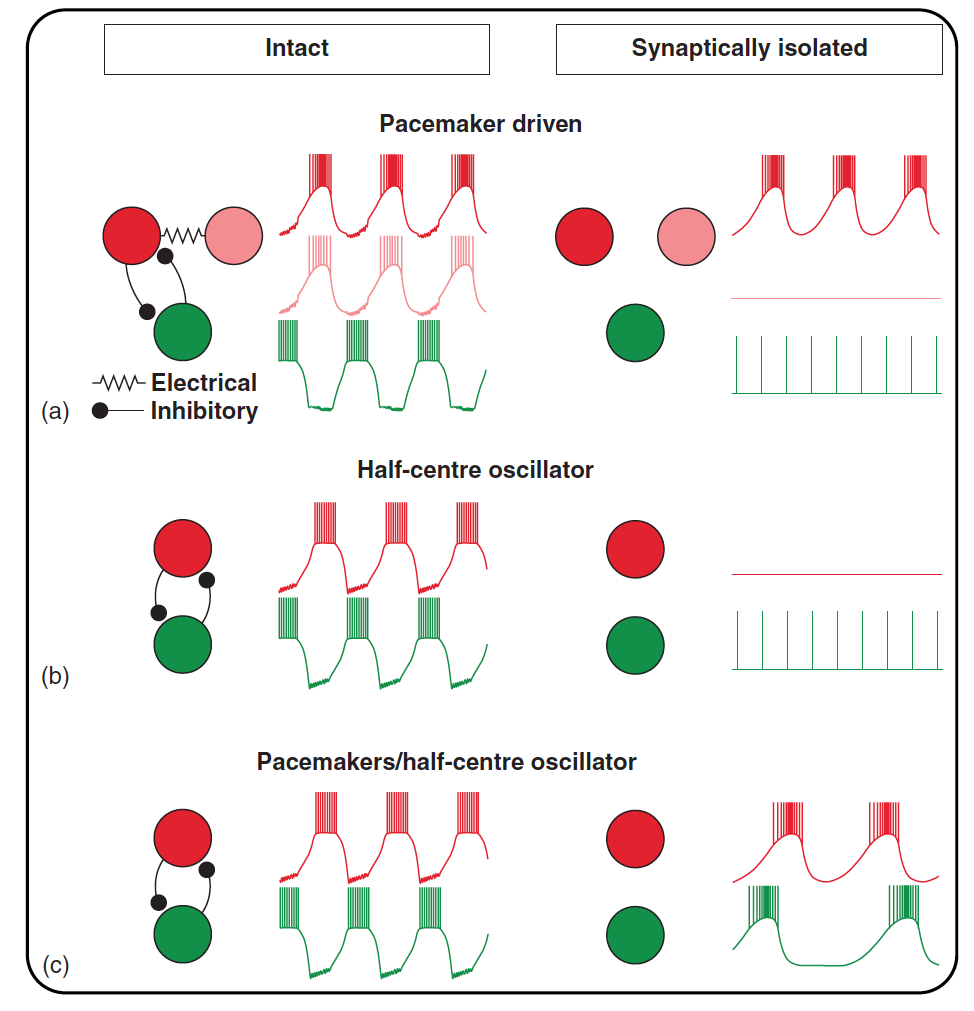

Fig. 36 Figure 2 from Bucher et al 2015 Mechanisms underlying rhythm generation.

Rhythmic neuron activity in the intact network (left) and after synaptic isolation (right).

a) Rhythm

generation can be based on endogenous oscillatory properties of a neuron (red). This neuron continues to burst in synaptic isolation, while an electrically

coupled member of the ‘pacemaker group’ (pink) and a follower neuron (green) fall silent or are tonically active.

b) In half-centre oscillations or other

network-based rhythm generation, bursting activity is usually not based on intrinsic oscillatory properties of neurons but emerges purely from synaptic

network interactions. In synaptic isolation, all network neurons therefore fall silent or are tonically active.

c) In some cases, stable and regular rhythm

generation may strongly depend on network interactions such as half-centre oscillations despite the presence of intrinsic bursting properties. In such cases,

synaptically isolated neurons may burst endogenously, but at slow frequencies and with irregular periods.¶

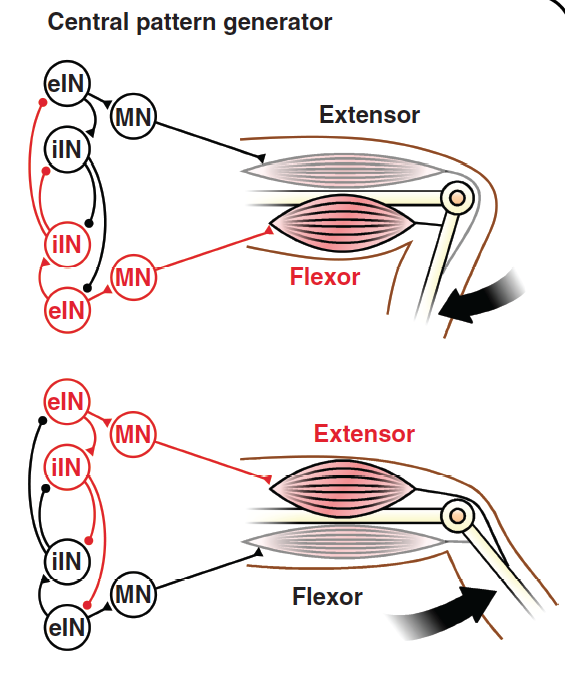

Fig. 37 Figure 1 from Bucher et al 2015 The basic version of rhythmic neural activity underlying repetitive motor behaviours is generated in the central nervous system by central pattern generators (CPGs). Rhythmic activity can be produced by mutually inhibitory connections between neurons controlling different muscles.¶

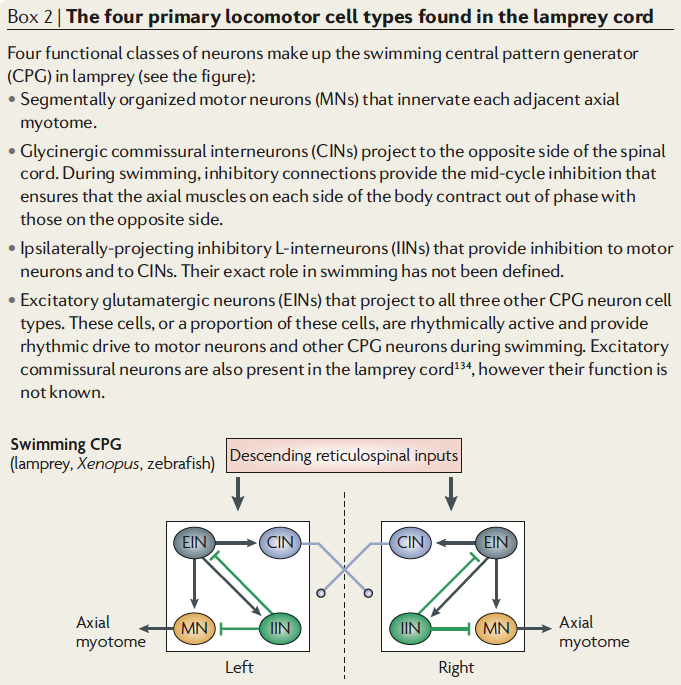

Fig. 38 From Goulding et al 2009¶

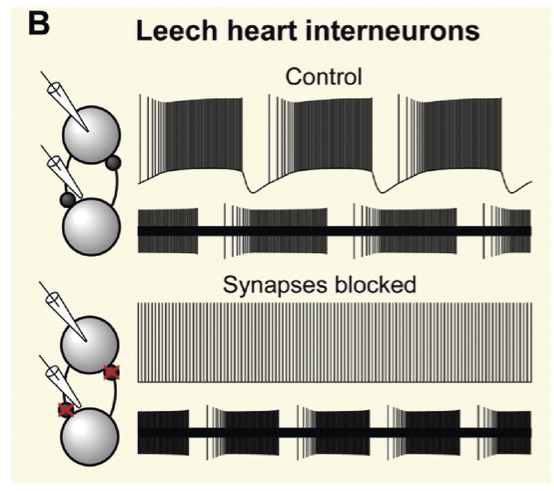

Fig. 39 Figure 1b from Marder et al 2005. Rhythmic activity in the leech heartbeat system was thought to arise from mutual inhibition of bilateral pairs of interneurons, because intracellular recordings (upper traces) show that these neurons fire tonically in the presence of synaptic blockers. However, rhythmic activity persists in the absence of synaptic interactions when a non-invasive extracellular recording method is used (lower traces).¶

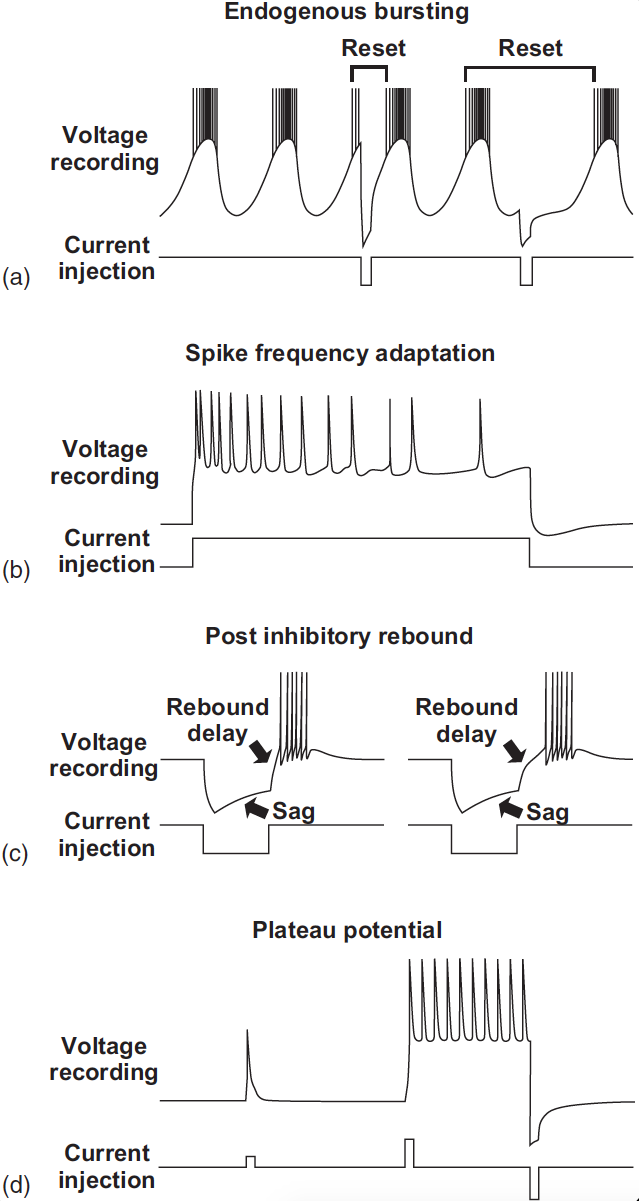

Fig. 40 Figure 3 from Bucher et al 2015 Common membrane properties of CPG neurons.

a) Endogenous oscillations (pacemaker properties). Current inputs can reset rhythmic activity,

either by advancing or delaying the next burst.

b) Spike frequency

adaptation is the waning of spike frequency during constant depolarizing

input.

c) Postinhibitory rebound is the ability to produce activity as a result

of prior inhibition. It is often accompanied by a sag potential, that is, an

escape from ongoing inhibition. The delay to the onset of the rebound burst

can be increased by fast potassium currents such as IA.

d) Plateau potentials

are relatively long-lasting firing responses to sufficiently large but short

depolarisations. They can either self-terminate or end in response to brief

hyperpolarizing input.¶

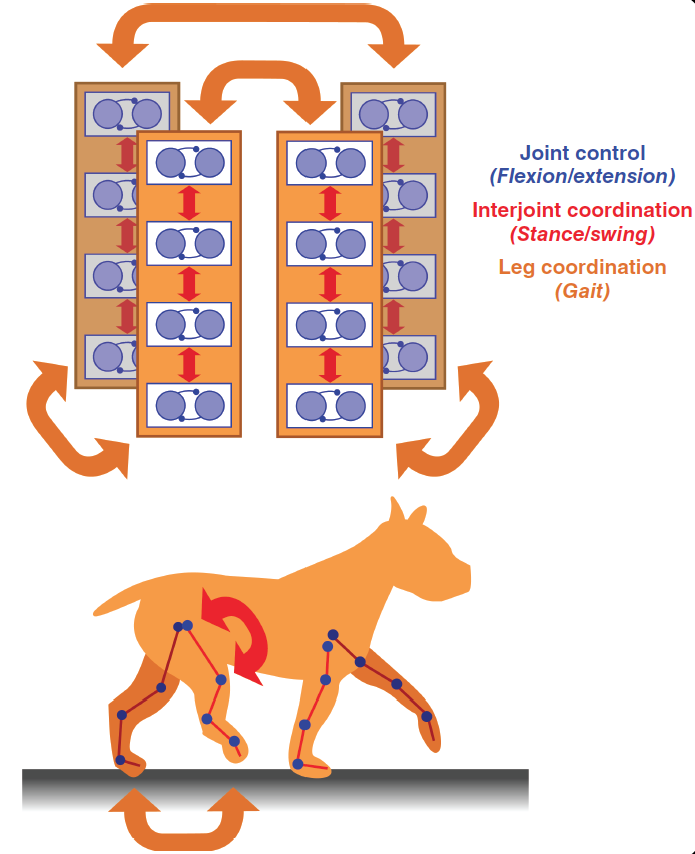

Fig. 41 Figure 5b from Bucher et al 2015 Modular organisation of motor patterns.

In walking animals, each leg joint has to be controlled by coordinating flexion and extension movements. All joints within one leg have to be

coordinated to achieve stepping movements in the proper sequence for stance and swing. All legs have to be coordinated to produce meaningful gaits.¶

Additional Resources¶

Ronacher, B. Innate releasing mechanisms and fixed action patterns: basic ethological concepts as drivers for neuroethological studies on acoustic communication in Orthoptera. J Comp Physiol A 205, 33–50 (2019).. This paper provides a framework for linking fundamental course concepts discussed so far

The Neural Control of Movement (2020) FULL BOOK. Edited by: Patrick J. Whelan and Simon A. Sharples

- 1

- 2

Image from molecular devices

- 3

Image from wiki

- 4

More detail on the mechanism of muscle activity for those interested in digging down another level of explanation. Motor neurons release acetylcholine from their axon terminals when their membrane potential goes above spike threshold. The post-synaptic receptors on muscle cells become permeable to sodium (Na+) when they bind acetylcholine. This leads to a cascade of depolarization that eventually triggers voltage-gated Calcium ion channels in the muscle cell. The increase in intracellular Calcium then enables a conformational change in the muscle fibers that shortens (contracts) the muscle (example mechanism in the margin image).

- 5(1,2,3)

Figure from Hediwg (2006) Pulses, patterns and paths: neurobiology of acoustic behaviour in crickets. J Comp Physiol A. Modified after Roesel von Rosenhof (1749).