Mating Systems

Contents

Mating Systems¶

Phenotype Diversity¶

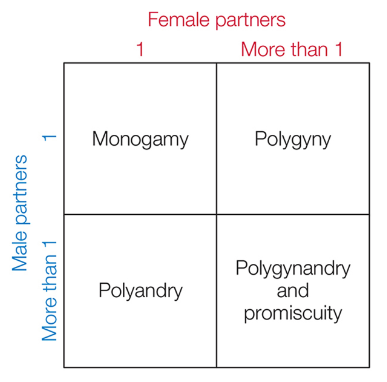

Animal mating systems are defined by the number of sexual partners that each sex has.

- monogamy¶

males and females pair off (either for a breeding season or for life)

- polygyny¶

males mate with multiple females, but females mate with a single male

- polyandry¶

females mate with multiple males but males only mate with a single female

- polygynandry¶

both males and females mate with multiple partners and long-term relationships form between the males and females

- promiscuity¶

both males and females mate with multiple partners but there is no formal association between mates beyond sperm transfer

The type of mating system that evolves will depend on which sex is limiting/limited and the degree to which the other sex can control resource access or monopolizes mates. Often, it seems that the distribution of resources influences the behavior of one sex and the behavior of that sex then influences the mating behavior of the other sex.

If members of the mate limited sex can limit access to the resources needed to survive and reproduce, then they could gain control over members of the limiting sex. Then, monopolization of access to the other sex seems like it would enable polygyny and polyandry to evolve.

Polygynandry seems more likely to evolve when neither sex can monopolize access to mates and when there are enough resources or territory to support a multi-sex group.

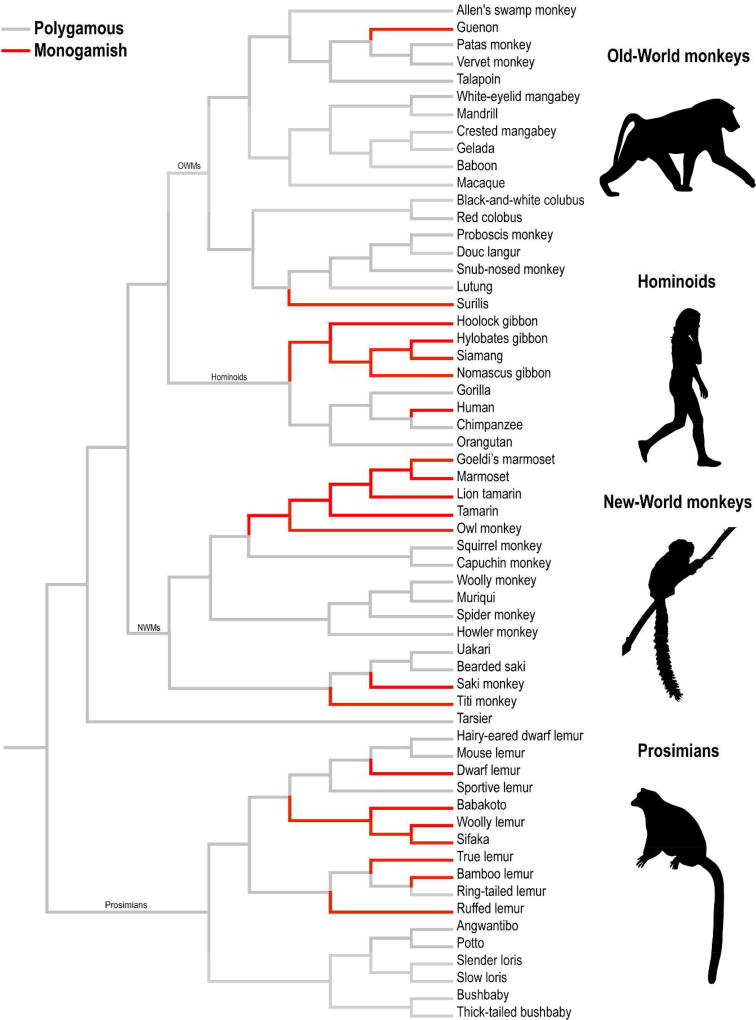

Monogamy seems to be a derived phenotype among many taxa, with many instances of convergence. For example, monogamy most likely evolved in humans and was not a phenotype exhibited by our last common ancestor with chimps.

Fig. 144 Evolution of polygamous and monogamous mating strategies across primates. Gray lines represent polygamous taxa; red lines represent taxa that show one or more social features associated with monogamy; i.e., “monogamish” (tip of the hat to Dan Savage). This primate phylogeny was assembled using data from 10kTrees (Arnold, Matthews, & Nunn, 2010) and visualized using Mesquite (Maddison & Maddison, 2001). Representative genera from Old-World monkeys (OWMs), Hominoids, New-World monkeys (NWMs), and Prosimiams are presented. Image from French et al (2018)1.¶

In some species, such as the side-blotched lizard that you examined in the context of evolutionary game theory, multiple mating system phenotypes exist in the same population.

Proximate Mechanisms of Monogamy¶

This section refers to the paper you read for class: Young et al (1999) Increased affiliative response to vasopressin in mice expressing the V1a receptor from a monogamous vole.

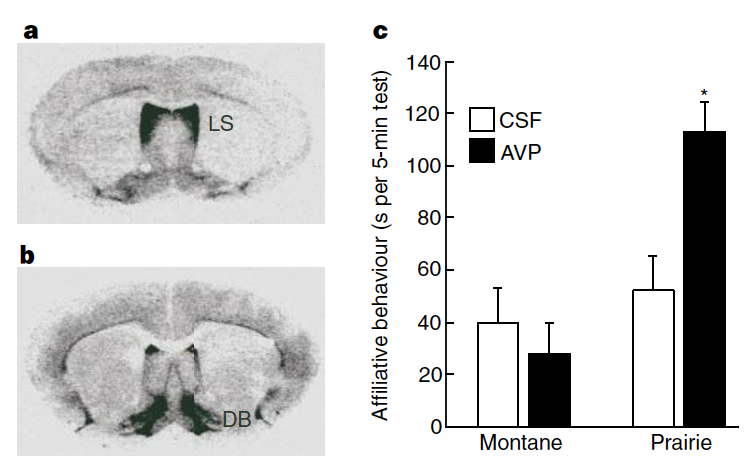

Prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) are monogamous and form long-lasting pair bonds. They also engage in extended biparental care after mating. Montane voles (Microtus montanus) are promiscuous and do not pair bond.

⏳ 25 min

Fig. 145 (Young et al Figure 1) Receptor autoradiography illustrates the different patterns of V1a-receptor binding in the brains of a, the non-monogamous montane vole, and b, the monogamous prairie vole. Note the high intensity of binding in the lateral septum (LS) of the montane vole but not the prairie vole, and in the diagonal band (DB) of the prairie vole but not the montane vole. Similar differences exist throughout the brain. c, Male prairie but not montane voles exhibit elevated levels of affiliative behaviour after vasopressin is administered directly into the brain (two-way ANOVA: species effect, F(1,27) = 10.3, P < 0.01; * Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test, P < 0.01 compared with CSF-treated prairie voles).¶

Q1: What defines “affiliative behavior” in this study?

Q2: What is a key piece of background information (previous experimental result) cited by Young et al as motivation for their study?

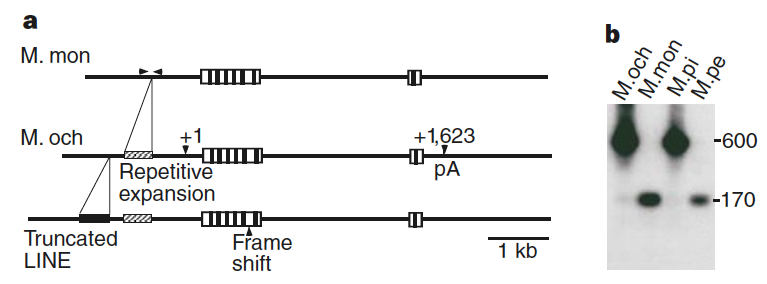

Fig. 146 (Young et al Figure 2) Transcription begins at +1 and polyadenylation (pA) occurs at +1,623 of the prairie vole gene. The boxed area within these sites represents the coding region and the vertical bars in the coding region represent the location of the transmembrane domains. Two distinct loci were isolated from prairie vole DNA. The sequences of the genomic clones have been deposited in GenBank (accession number AF069304). b, PCR amplification of genomic DNA using primers on either side of the expansion (arrows in a) demonstrates the presence of the expansion in monogamous prairie and pine (M. pi) voles (600-bp band), but not in promiscuous montane or meadow (M. pe) voles.¶

Q3: What hypothesis is being tested by the experiment in Figure 2?

Q4: In Figure 2, are they testing the sequence or the spatial brain expression of the V1a receptor gene?

Q5: What is microsatellite DNA, generally? Which resource(s) did you choose to consult for this information after searching?

Q6: In the context of this study, how would you define the function of microsatellite regions of DNA?

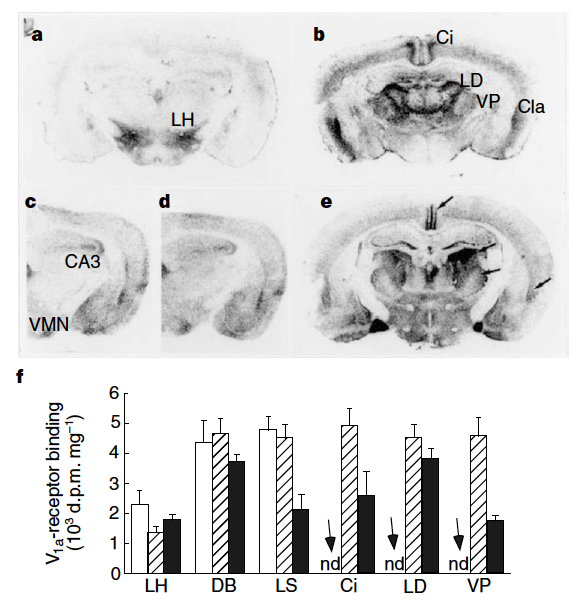

Fig. 147 (Young et al Figure 3) Receptor autoradiography illustrates the distribution of V1a-receptor binding in wild-type (a) and transgenic (b) mice. Although V1a-receptor binding is altered, oxytocin-receptor binding is identical in wild-type (c) and transgenic (d) mice. Binding in the cingulate cortex (Ci), laterodorsal (LD) and ventroposterior (VP) thalamic nuclei, claustrum (Cla) and several other regions of transgenic mice is similar to that found in the brain of the prairie vole (e). f, Quantification of V1a-receptor binding in wild-type mice (open bars), transgenic mice (striped bars) and prairie vole (filled bars) (n = 6–7 per group) demonstrates that receptor density in transgenic mice is not elevated in areas that normally express receptors in mice (for example, lateral hypothalamus (LH), diagonal band (DB) and lateral septum (LS); nd indicates no detectable specific binding in wild-type mice.¶

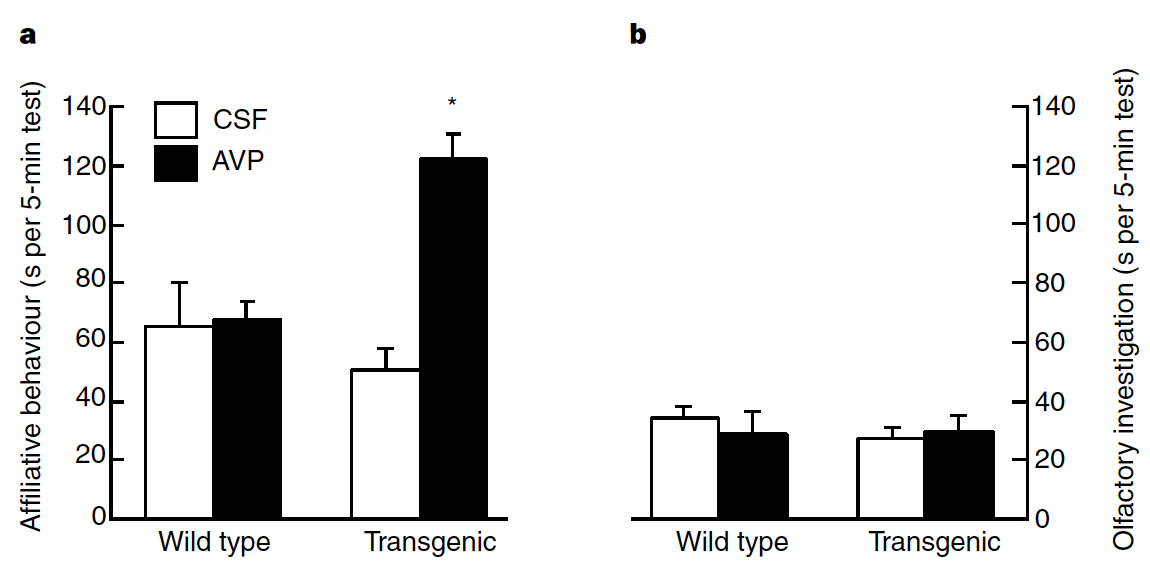

Fig. 148 (Young et al Figure 4) a, AVP increases the duration of affiliative behaviours directed towards an ovariectomized female in male transgenic mice with a prairie vole pattern of V1a-receptor expression, but not in male wild-type mice (two-way ANOVA: genotype effect, F(1,22) = 4.3, P < 0.05; * Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test, P < 0.01 compared with CSF-treated transgenic animals). b, AVP has no effect on olfactory investigation of cotton balls soiled with bedding from an ovariectomized female’s cage in either transgenic or non-transgenic males.¶

Q7: What hypothesis is being tested in Figure 3 and 4 together? Contrast this with the hypothesis tested in Figure 1.

Q8: What is the purpose of the experiment/results shown specifically in Figure 3?

Q9: In the context of this study, why was it important to show the results of the experiment in Figure 4b?

Q10: In summary, how would you describe the neural, hormonal, and genetic mechanisms of monogamy?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

So… it seems the inference is that the circuit for pair bonding exists in wildtype mice, but is not activated by AVP. In other words, that circuitry could be phylogenetically older than pair bonding (in voles). What is that circuit normally activated by and what is it normally used for?

The Evolution of Monogamy¶

Parental Care Hypothesis¶

Hypothesis: Offspring that need a lot of care put selective pressure on paternal care and therefore monogamy.2

This hypothesis was the prevailing model for a long time.3

All else being equal, it makes sense for a male (in species where the male is more reproductively available than the female) to monopolize as many females as possible rather than remaining monogamous. In other words, optimal mating rates for males would be higher.

However, game theoretic models would predict that promiscuous male competitors and the risk of cuckoldry (raising someone else’s offspring) limit the scope for the evolution of male investment. In other words, cheating phenotypes would have a higher fitness in a population of monogamous males. Because male investment likely would have resulted in male absence (e.g., through resource provisioning), caring males would have faced potential fitness costs due to freerider males that ‘steal’ paternity.

Additionally, growing evidence suggests that paternal care evolves only after monogamy becomes established in a population.

Partner Availability Hypothesis¶

Hypothesis: Dispersed or rare females put selective pressure on monogamy directly.2

For example, solitary females that are dispersed across a landscape (due to resource dispersal and/or female intolerance) limit multiple mate monopolization opportunities for males and favor monogamy as a consequence.

However, the hypothesis also applies generally to the situation in which the mating pool is male-biased, and males face difficulty in finding additional mates. A current partner becomes a valued resource, favoring mate guarding behavior to assure paternity. Therefore, the operational sex ratio is a key factor in fitness payoffs for evolutionary models of mating strategies.

Under assumed ancestral human conditions, it seems that male mate guarding, rather than paternal care, drives the evolution of monogamy, as it secures a partner and ensures paternity certainty in the face of more promiscuous competitors.4 It is not always true (as has been previously concluded) that males benefit more from mating multiply. Instead, a growing body of literature highlights that partner rarity intensifies male commitment to pairbonded strategies, rather than multiple mate-seeking, across populations of both human and nonhuman animals.

For details of a model that considers all of these factors (offspring survival benefit of parental care, probability of mating given the operational sex ratio, risk of cuckoldry, conception rate of females, and male survival), see Schacht and Bell (2016)4.

Additional Resources¶

Turner et al 2010 Monogamy evolves through multiple mechanisms: evidence from V1aR in deer mice Mol Biol Evol. 2010 Jun;27(6):1269-78.

- 1

French et al (2018) Social Monogamy in Nonhuman Primates: Phylogeny, Phenotype, and Physiology

- 2(1,2)

Remember, that this statement assumes that the operational sex ratio is skewed toward males (males are mate limited by lack of reproductively available females). The opposite can be true, in which case maternal care would be in question.

- 3

- 4(1,2)