Communication: Proximate

Contents

Communication: Proximate¶

⏳ 5 min

Q1: How would you define communication?

Q2: In order to achieve communication, what steps/processes in the sender and the receiver need to be fulfilled by proximate mechanisms?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Acoustic¶

Sender: motor patterns¶

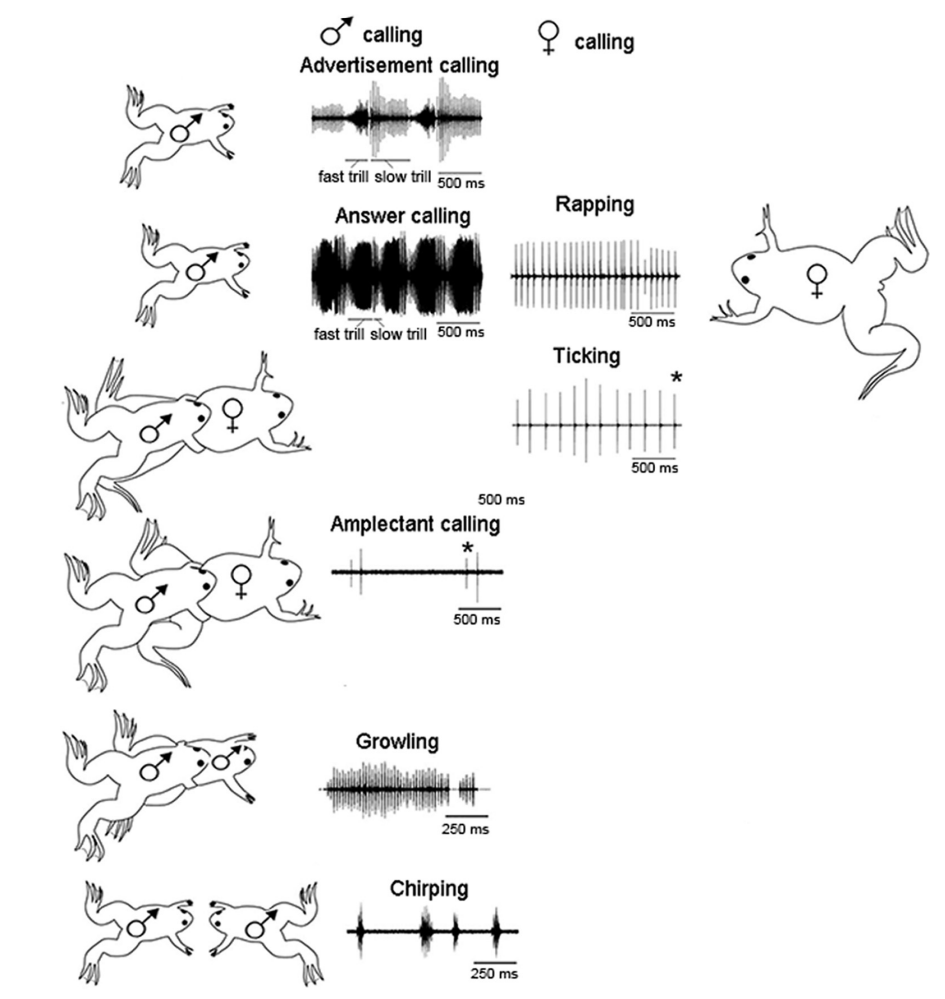

Xenopus is a frog genus in which the mechanisms and evolution of acoustic communication has been extensively studied.

The basic vocal unit of all Xenopus calls is a brief sound pulse. Each pulse is generated by two “arytenoid discs” in the larynx being rapidly pulled apart (rather than air moving through the larynx). These pulses are then combined into a variety of temporal patterns that have specific social meanings.1

The male advertisement call consists of individual sound pulses at fast (60 pps) and slow (30 pps) rates. Males produce advertisement calls when alone or with conspecifics.

The female rapping call consists of a rapid (16 pps) series of sound pulses. Females produce rapping when oviposition is imminent. Rapping serves as an acoustic aphrodisiac and stimulates male answer calling.

The female ticking call is a slower (6 pps) series of pulses. Females extend their hind legs and produce ticking when clasped.

A male clasping another frog, male or female, produces the amplectant call.

A clasped male responds with growling.

During the social interactions that precede one male vocally suppressing another, males produce the chirping call.

Fig. 107 Sound pressure waves from the vocal repertoire of X. laevis. Vocalizations are specific to social context and sex.2 Modified from Zornik and Kelley, 2011. pps: pulses per second.¶

The hormone serotonin (5-HT) plays a crucial role in initiating vocalization. Bathing the isolated brain in serotonin evokes vocalization motor patterns (measured from the vocal motor nerve). In the intact animal, elevating endogenous serotonin levels using a serotonin “reuptake inhibitor” increases vocalization output as well. This mechanism is shared by the sexes despite the differences in the actual vocalizations between males and females. Bathing the brain in serotonin evokes male-specific vocalizations in males, but female-specific vocalizations in females.

⏳ 5 min

Q3: Identify/describe a proximate mechanisms (neural, genetic, hormonal, developmental) that you hypothesize could explain sex differences in Xenopus vocalizations versus a proximate mechanism that is likely shared.

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

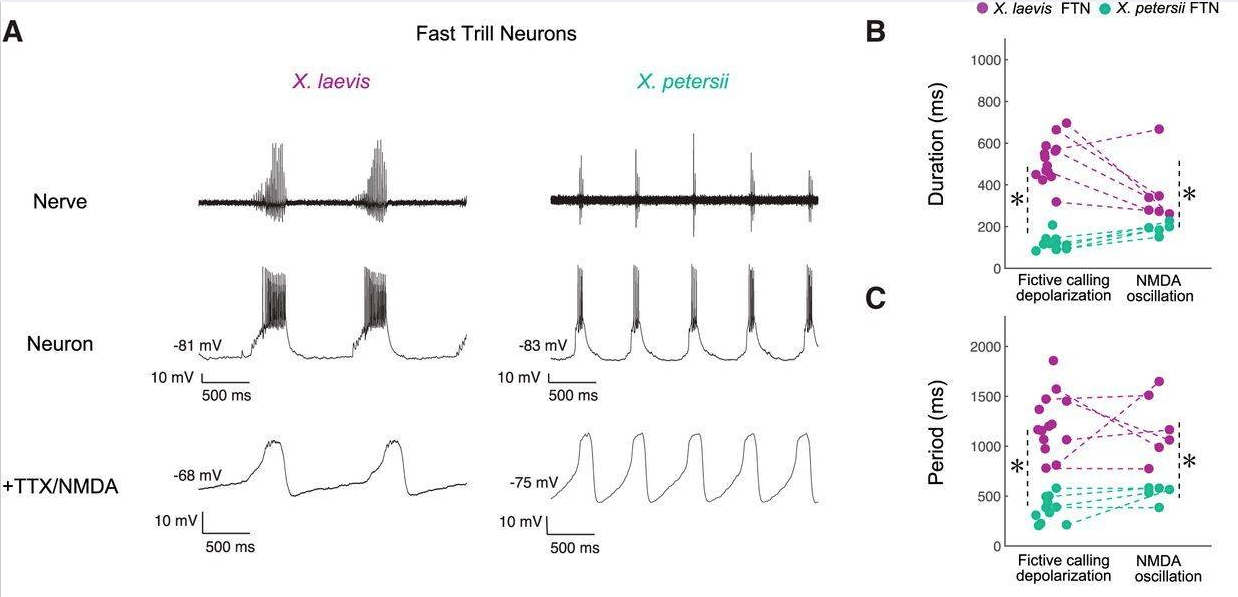

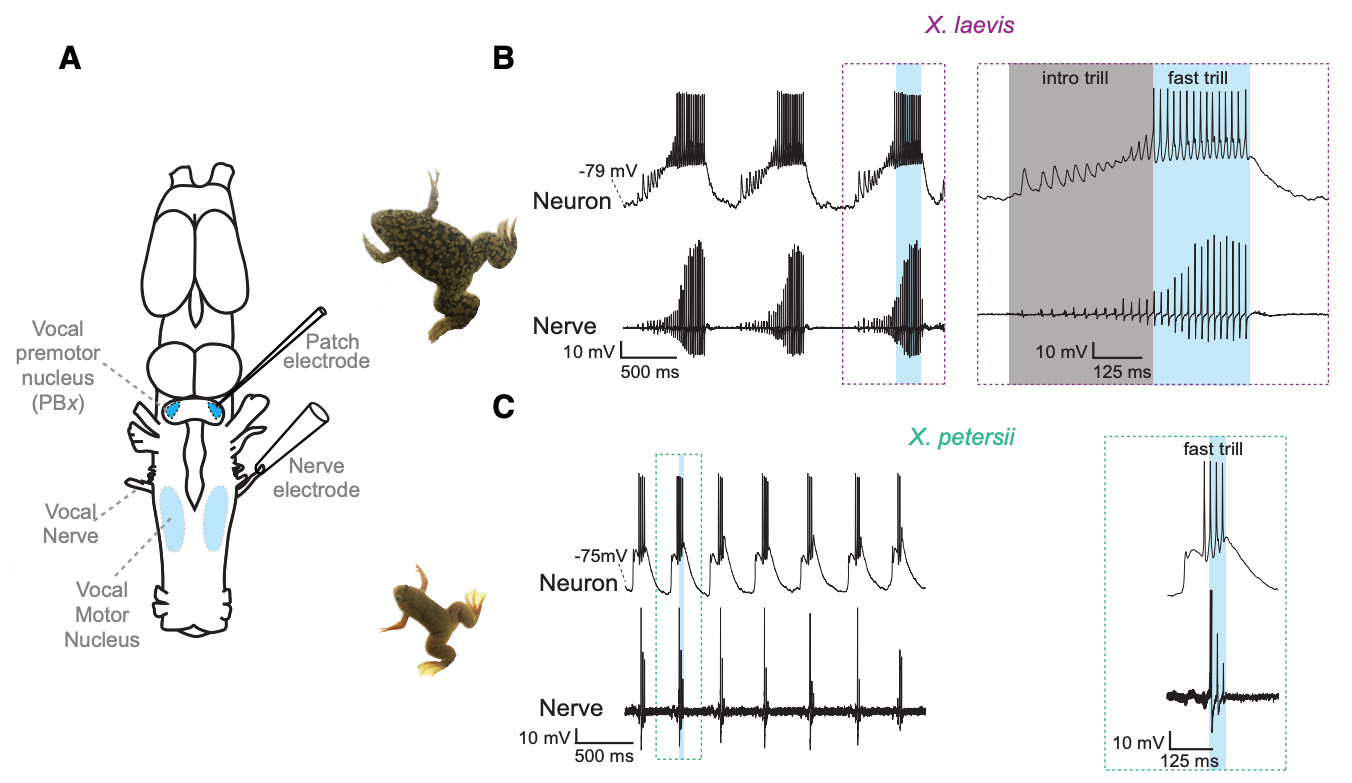

In Xenopus, the central pattern generators responsible for generating the vocalization motor patterns have been identified (CPGs; a network of neurons that generates patterned motor output without sensory feedback).

In all Xenopus species, a combination of several different voltage-sensitive ion channels make the membrane potential of CPG neurons oscillate endogenously when provided with a steady (unpatterned) command input. Remarkably, differences in intrinsic membrane properties of vocal CPG neurons explain differences in species-specific vocal patterns.

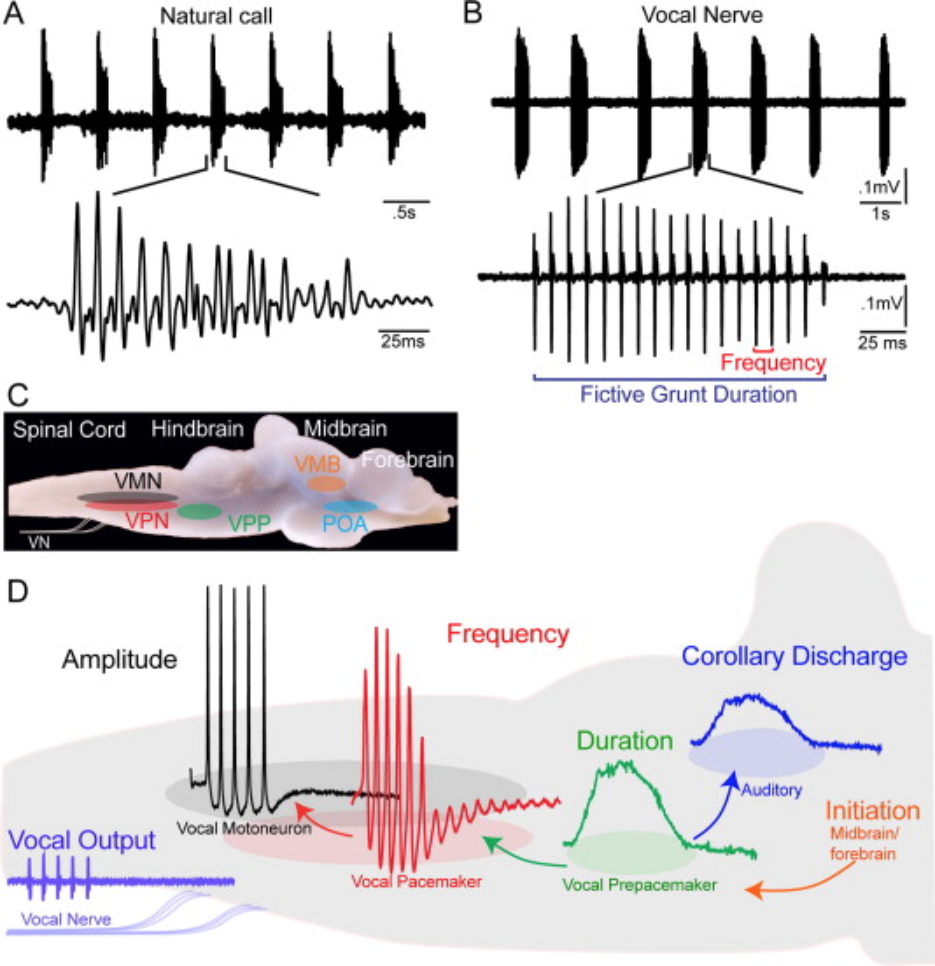

Fig. 108 A vocal CPG underlies divergent vocalizations in X. laevis and X. petersii. The vocal motor nucleus (VMN) contains motor neurons that project to vocal muscles in the larynx (the vocal effector organ). Voltage spikes in the vocal nerve exactly match the temporal features of the vocalizations. Premotor neurons in the Parabrachial Nucleus (PB) project to the vocal motor nucleus. The PB neurons of different species have different endogenous oscillation patterns.3¶

The location and electrical properties of vocal CPG neurons (and the synaptic connections among them) in midshipman fish have been identified. You are already familiar with the mating “humming” of midshipman fish. Two other types of vocalizations that they produce are grunts and growls.

The midshipman vocal CPG also utilizes endogenously oscillatory neurons. However, unlike in Xenopus, the call frequency and duration are controlled by separate neuron types in separate locations of the brain.

Fig. 109 Collectively, the Prepacemaker-Pacemaker-Motorneuron circuit is referred to as the vocal CPG. Nuclei within forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain vocal-acoustic centers form part of a descending vocal system that includes links with the auditory system and controls vocalization initiation. A copy (“corollary discharge”) of the vocalization duration signal get sent to auditory input regions of the brain as well.¶

⏳ 5 min

Q4: Why do you think a copy (“corollary discharge”) of the vocalization duration signal get sent to auditory input regions of the brain in addition to motor output regions?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Receiver: pattern recognition¶

How are received communication signals perceived and identified correctly?

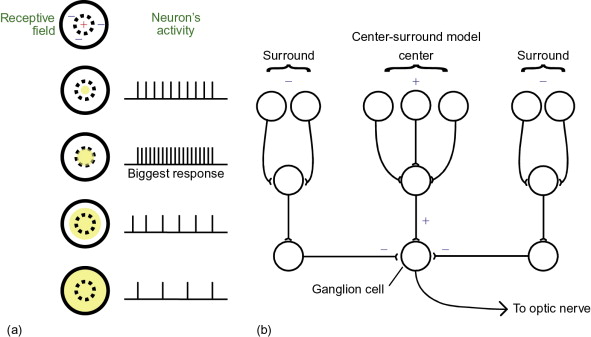

At the periphery sensory receptor neurons are tuned to very basic stimulus features (like one frequency of sound or light at one small location in space).

In the brain, there are neurons that are tuned to specific stimulus patterns. This tuning is created progressively. Along a sensory processing pathway, cells are optimally activated by an integrated combination of simpler receptive fields.

Receptive field tuning is a bit easier to understand in the visual system than the auditory system.

In the retina, photoreceptor neurons are each tuned to light/dark at a specific location in space. This spatial tuning is determined by the physical location of the photoreceptor on the retina. Photoreceptor outputs then converge in specific combinations so that Retinal Ganglion Cells (RGCs) are tuned to more complex features/shapes.

Fig. 110 A classic Retinal Ganglion cell’s center-surround visual receptive field is constructed from a synaptic combination of a set of photoreceptor neurons (top row of the network shown) that are themselves tuned to light at various locations in space.¶

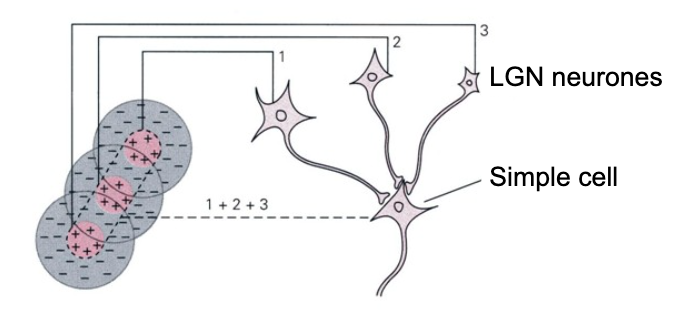

RGCs then converge onto “simple cells” in the thalamus (LGN) to create even more specialized receptive fields. Simple cells are no longer able to be activated by light at one location in space like the photoreceptors were. Simple cells are tuned to edges of light oriented at specific angles in space

Fig. 111 A neural network for the simple cell receptive field in the LGN (lateral geniculat nucleus), which receives converging input from retinal ganglion cells each tuned to specific center-surround receptiv fields.¶

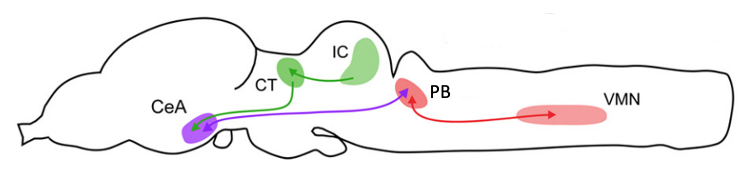

How is perception linked to production? The categorization of sensed communication signals must be followed by the activation of neural circuits that can generate an appropriate communication response.

The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) is a strong candidate for a role in auditory-guided vocal communication in Xenopus. It receives input from the auditory processing pathways of the brain and projects to parabrachial nucleus (PB; where CPG neurons are located).

In Xenopus, researchers have shown that CeA is a key brain area that links auditory and vocal production circuits to match socially appropriate vocal responses to acoustic features of male and female calls.

Damage to the CeA results in socially inappropriate responses of males to female, but not to male, calls. Normally, female rapping vocalizations evoke answer calling in males. In males with damage to the CeA, female rapping evokes prolonged vocal suppression. Prolonged vocal suppression should only be evoked by the calls of dominant males, not rapping. Even when tested with an actual rapping female, males without a CeA do not answer call.4 Males with damaged CeA do call spontaneously (so they are not mute). They also respond to male advertisement calls with prolonged vocal suppression, so they are not deaf and can produce the socially appropriate response to a dominant male.

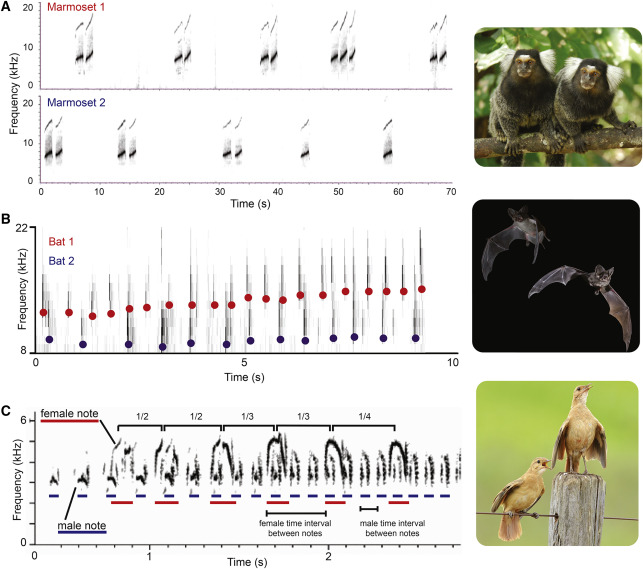

Turn-taking¶

Turn-taking and inter-personal coordination of action timing in general, is critical for communication. This behavior is ubiquitous across both vocal learners and non-learners.

The function of this behavior is not clear, but there are many possibilities including: group cohesion, avoidance of “jamming” each other’s signals, dominance/submissive displays, and sexual selection.

Turn-taking requires precise coordination of the timing of signals between individuals. With the proponderanc of Zoom communicaiton, we can relate to how disruptions of the timing of auditory cues (like those annoying delays caused by poor connections) make effective communication difficult and frustrating. How do the brains of two individuals synchronize their activity patterns for rapid turn-taking during effective and attractive vocal communication?

Daniela Vallentin, a recearcher currenlty working at Max Plank in Germany, investigates the neural mechanisms of this remarkable feat in birds.

Neural Control of Vocal Interactions in Songbirds (particularly minutes 2-12 for the general setup).

Learned versus Innate Communication Signals¶

The behavioral trait typically studied as “vocal learning” involves “the influence of auditory information, including feedback, on vocal development” (Nottebohm, 1972).

Vocal-learning species share the presence of:

a critical period for learning

babbling

deafness-induced deterioration of learned vocalizations

dialects

brain circuits that control production and learning of vocalizations.

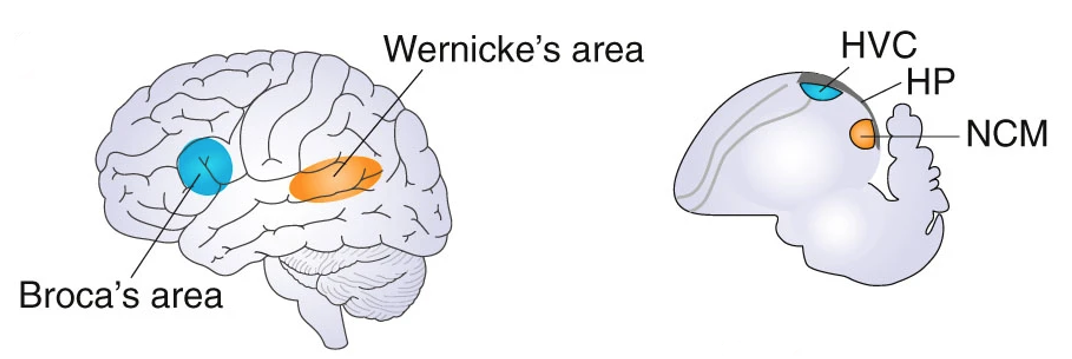

In humans, there is a dedicated “language” brain network involving multiple circuits. It is well established that Broca’s area in the left frontal lobe and Wernicke’s area in the left temporal lobe are central brain regions in this network. Among other functions, Broca’s area is involved in speech production and language syntax, while Wernicke’s area plays a major role in speech perception and comprehension.

In the songbird brain, there is a dedicated “communication” brain network with similar neural dissociation between song production (the ‘song system’, including the song nucleus HVC, used as a proper noun) and song perception (including the caudomedial nidopallium, NCM). In a functional sense, these networks in songbirds are considered to be analogous to Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas in humans, respectively.6

Fig. 113 Similar critical brain regions underlying auditory communication in humans (left) and songbirds (right).¶

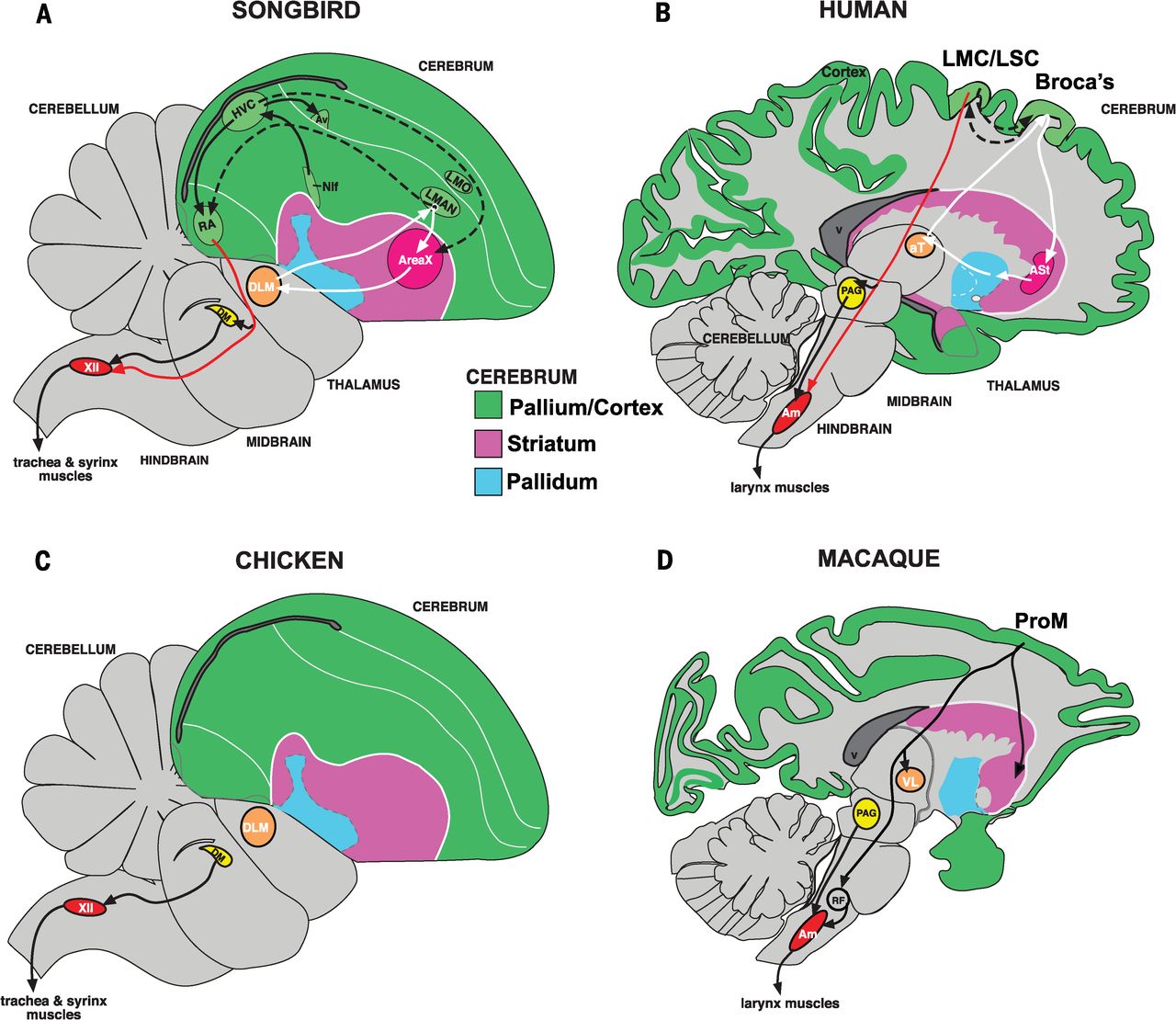

More specifically, vocal-learning brain circuits include striatal (Figure 113, pink) as well as cortical (Figure 113, green) vocal brain regions, a loop of synaptic connections among cortical and striatal regions (Figure 113, white arrows), and a unique direct connection from motor cortical areas (human laryngeal motor cortex (LMC) and songbird robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA)) to brainstem vocal motor and respiratory neurons for phonation (Figure 113, red arrow).

Fig. 114 Sagittal (looking sideways at the head) slices of the brain of humans and song-learning birds ( ie. songbird, parrot, and hummingbird) as well as vocal-nonlearning nonhuman primates (macaque) and birds (dove and quail).

Songbird Area X, a striatal region necessary for vocal learning, is most similar to a part of the human striatum activated during speech production. The RA (robust nucleus of the arcopallium) analog of song-learning birds, necessary for song production, is most similar to laryngeal motor cortex regions in humans that control speech production. Red arrows show the direct projections found only in vocal learners, from vocal motor cortex regions to brainstem vocal motor neurons. Forebrain song nuclei are absent in vocal non-learning species.7¶

Mechanisms of learning¶

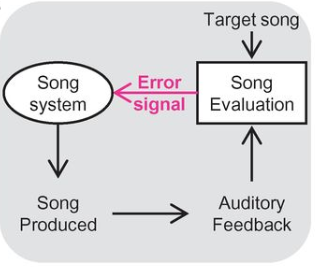

In order to learn vocalizations, an animal needs both a tutor and a way to compare the tutor’s vocalizations to their own attempts. A general circuit concept has been hypothesized, but its implementation in brain circuits is still mostly illusive.

Fig. 115 Evaluation of auditory feedback during singing is hypothesized to result in “error” signals that reach the song system.¶

In the brain of the sender, dopamine activity is suppressed when learned communication signals are worse than predicted, and activated when learned communication signals are better than predicted.8 Therefore, dopamine could provide a teaching signal for vocal learning.

Visual¶

Fig. 117 The fear grin is a facial expression that signals submission. The fear grin is used by young chimpanzees when approaching a dominant male in their troop (hypothesis: it indicates they accept the male’s dominance). Image credit: The ‘fear grin’ by CK-12 Foundation, CC BY-NC 3.0¶

Fig. 118 The bright coloration of some toxic species, such as the poison dart frog, acts as a do-not-eat warning signal to predators.¶

Olfactory¶

Fig. 119 This diagram shows pheromone trails laid down by ants to direct others in the colony to sources of food. When a food source is rich, ants will deposit pheromone on both the outgoing and return legs of their trip, building up the trail and attracting more ants. When the food source is about to run out, the ants will stop adding pheromone on the way back, letting the trail fade out. Image credit: Knapsack ants by Dake, CC BY 2.5¶

Additional Resources¶

The Xenopus Amygdala Mediates Socially Appropriate Vocal Communication Signals Ian C. Hall, Irene H. Ballagh, Darcy B. Kelley Journal of Neuroscience 4 September 2013, 33 (36) 14534-14548; DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1190-13.2013

Hubel & Wiesel’s demonstration of simple, complex and hypercomplex cells in the cat’s visual cortex

- 1

Because of its evolutionary history of return to water from land, Xenopus have evolved a specialized mechanism of sound production within the larynx. The sound-producing elements are two tightly apposed arytenoid cartilage discs at the anterior end of the larynx. Action potentials of axons in laryngeal nerves leads to simultaneous contraction of paired bipennate muscles connected to the discs by tendons. Contraction generates rapid separation of the discs, which creates a single pulse of sound as the larynx vibrates within the thorax, effectively coupled to the body and the surrounding water.2

- 2(1,2)

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Convergent transcriptional specializations in the brains of humans and song-learning birds

- 8(1,2)