Components

Contents

Components¶

Why?

To ask why and how, we must define what. What is animal behavior? This workbook explores its composition and organisation.

Day 1; Responses template for use on computer if desired (“Save a Copy to Drive” to edit and save your work)

Day 2; Responses template for use on computer if desired (“Save a Copy to Drive” to edit and save your work)

Units of behavior¶

Why?

Attention to the way we define behavior for a particular study must include considering the appropriate organizational level and timescales for our level of analysis and our question (ultimate versus proximate, neural versus genetic, etc).

⏳ Take 5 minutes to complete the next section

Fundamental units of …¶

All living organisms are made up of cells.

Q1: What are several different types of cells can you think of?

Q2: Organize the following terms according to a hierarchy of (nested levels of) composition: cells, organs, bodies, organ systems and tissues.

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

⏳ 10 min

Cells are considered the fundamental unit of life. You can use this model from biology to explore the analagous concept in the study of animal behavior.

Q3: What nested levels would you split behavior into? Create a name for, and describe, each level. It can help to think of an animal and some of its behavior to use as an example of your categorization and organization.

Q4: In your model, what are the fundamental units of behavior? Provide some examples.

Q5: What timescale do these fundamental units of behavior generally occur over?

Q6: What is the timescale of behavior at the highest level you categorized?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Movemes, Actions, Activities¶

The nested levels of organization that you just explored are examples of hierarchy. The hierarchical nature of behavior seems clear, despite a lack of concensus for terminology used to describe its component parts12.

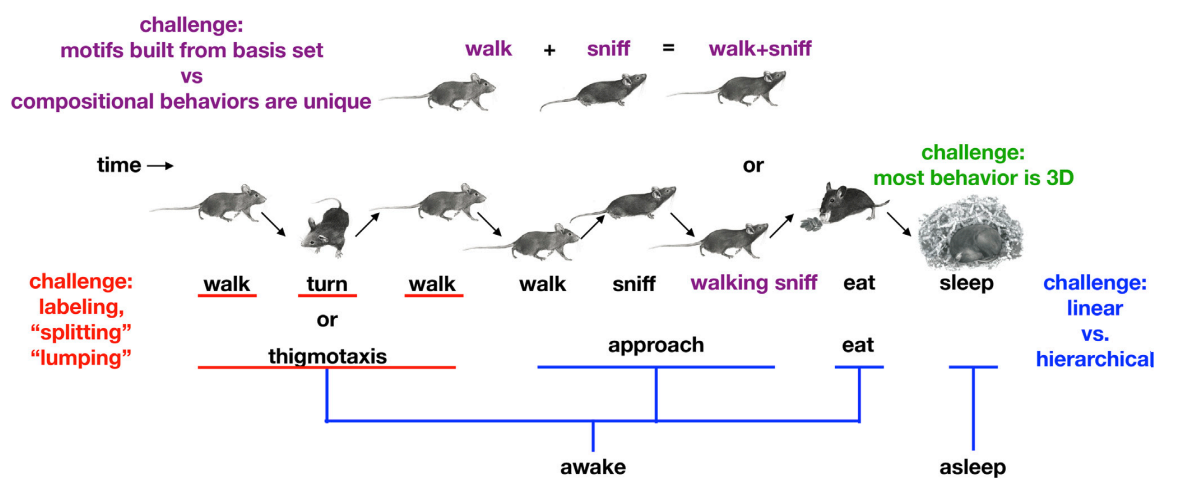

The following figure depicts and describes challenges that arise from the hierarchical nature of behavior that we need to grapple with when we study it.

Fig. 2 Center (mouse cartoons): A characteristic sequence of behaviors exhibited by a mouse in its home cage as it moves around the walls (thigmotaxis), approaches some food, eats, and then sleeps. Several key challenges facing any segmentation of continuous behavior into components are illustrated, including the following two points.

1) Behaviors need to be labeled, which raises the problem of lumping versus splitting (red); for example, mice engage in thigmotaxis (behaviors in which the mouse exhibits locomotion and turning behaviors that are deterministically sequenced to generate an action where the animal circumnavigates its cage). Is thigmotaxis a singular or unitary behavior (because its elements are deterministically linked during its expression), or it is a sequence of walking, turning, and walking behaviors?

2) Should behavior be considered at a single timescale that serially progresses or instead considered a hierarchical process organized at multiple timescales simultaneously (blue)? When the mouse is sniffing and running at the same time, is that a compositional behavior whose basis set includes run and sniff, or is running+sniffing a fundamentally new behavior (purple)?2¶

The following language, as defined by Anderson and Perona1, provides a reasonable basis for discussion of the hierarchical nature of behavior.

- Moveme ¶

The simplest meaningful pattern associated with a behavior. Typically involves a short, ballistic trajectory described by a verb, such as a turn, a step, or a wing extension, which cannot be further decomposed. It is analogous to a phoneme in language.

- Action ¶

A combination of movemes that always occurs in the same stereotypical sequence and that is also described by a verb. Examples of actions include walk (step + step + step), thigmotaxis (walk + turn + walk), etc. In language, it would be analogous to a word or to an idiomatic expression.

- Activity ¶

A species-characteristic concatenation of actions and movemes whose structure is typical, ranging from stereotyped to variable. Variability can be observed both in the structure or dynamics of the individual actions that comprise an activity, as well as in the timing and/or sequence of the actions. Examples of activities include nest-building, parenting, etc.

⏳ 15 min

Q7: How would you define ‘hierarchy’ in the context of animal behavior?

Q8: How do these categories defined by Anderson and Perona map onto the categories that you came up with earlier? Any thoughts?

Q9: Pick an animal that you are familiar with (do not spend too much time deliberating over which animal to use). Make an example behavior hierarchy for that animal using either your group’s own hierarchical categories, or the “moveme, action, and activity” hierarchical categories. Do not include all behavior of the animal, just enough to make an example hierarchy of behavior. Diagram the behavior hierarchy and define each behavior that you included at each level. (Do not use any of the examples already given in the figure above).

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Fixed Action Patterns (FAP)34, Releasing Mechanisms, and Sign Stimuli¶

Why?

Once you have defined individual behaviors, you can determine what behavior an animal is doing at each moment in time. AND what that animal is not doing at that moment in time. Essentially, behaviors compete for expression and an animal’s motivation, its life history, and its external environment determine which wins. The Nobel laureate Konrad Lorenz laid the foundations for an approach to studying animal behavior and categorized behavior into Fixed Action Pattern components that are released by Sign Stimuli.

- Fixed Action Patterns (FAPs) ¶

In a general sense, FAPs are identifiable behaviors. Historically, the term FAP has been used to mean instinctive, but that distinction may not be so necessary/useful5. At an extreme, FAPs are very stereotyped.

Egg Rolling is a common example of FAPs used in introductory animal behavior courses. Female gulls sit on their eggs in the nest to incubate them. Sometimes, the eggs roll out of the nest. The gull, noticing an egg outside of the nest, performs the egg rolling behavior in response. As a class, let’s watch these two videos of egg rolling:

⏳ 10 min

Q10: Based on the video, define the gull ‘egg rolling’ behavior objectively.

Q11: What do you think the function of egg rolling behavior is?

Q12: What else do you notice in these example videos of egg rolling behavior? List comments and questions that you have.

⏹️ STOP here for today.

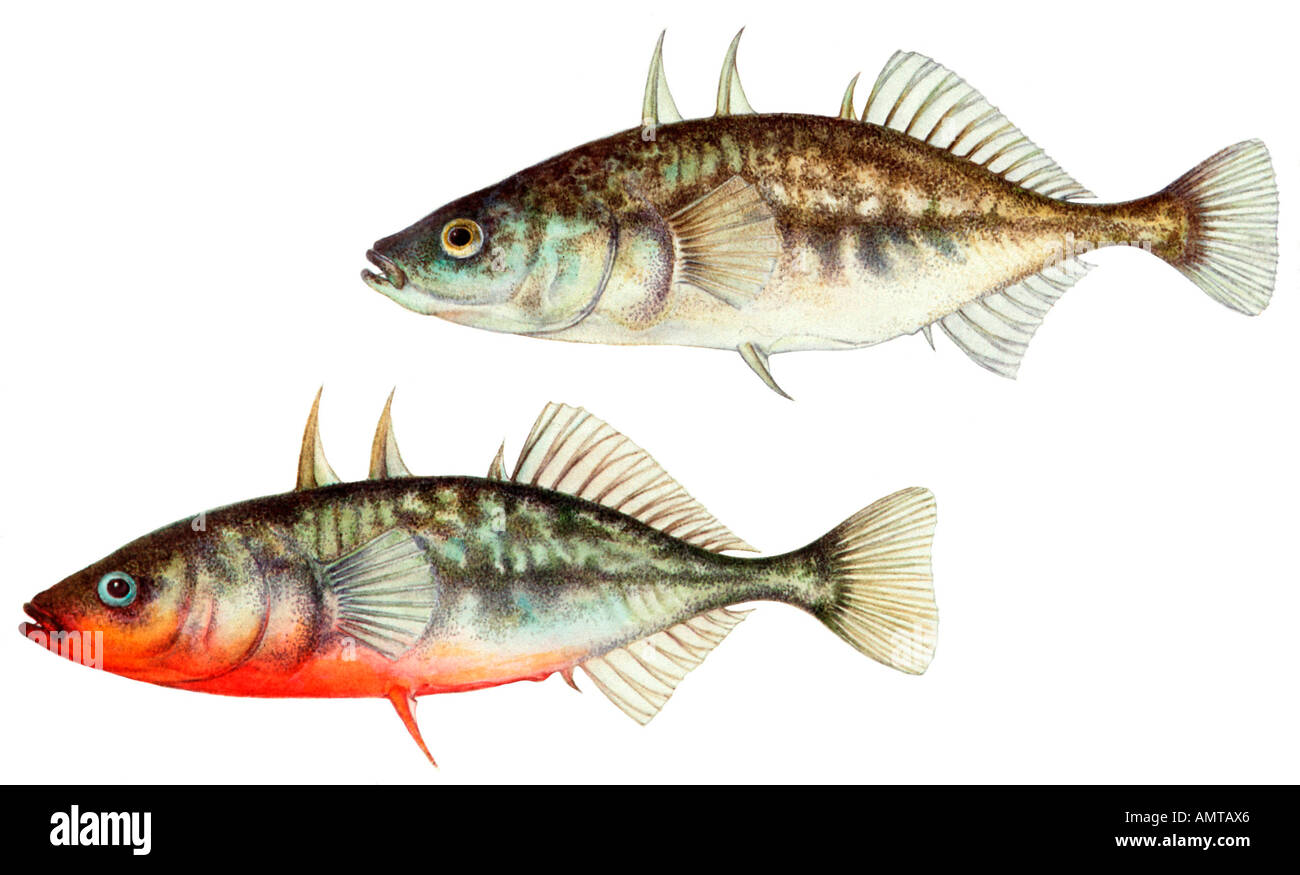

Territorial aggression behavior in stickleback fish is another common “introductory animal behavior course” example of FAPs6. During the breeding season, the male fish select a territory on which they build a nest. When a male stickleback spots another nearby male in his nesting territory, he will launch into FAP aggressive displays designed to scare off the stranger. However, males are not aggressive to nearby females in their territory.

Fig. 3 Stickleback fish appearance. Top: female. Bottom: male.¶

⏳ 5 min

Q1: If aggressive FAPs should only be directed toward other males, what sensory cues could be used to appropriately trigger (or suppress) FAP expression?

To test what stimulus (sensory cues/features) triggers aggression FAPs, we need to quantify the behavior somehow. A bite is a component of aggression, and a commonly used measure of aggression is bite rate. For this study, let’s define a bite as contact of the male’s mouth against an object.

Q2: Mathematically define ‘bite rate’ (ie. how would you calculate it?).

Q3: If bite rate was a good metric of aggression, would you predict that the bite rate of a male stickleback fish would be higher in the presence of another male or another female?

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

As a class, let’s watch this video of an experiment on stickleback aggression. As you watch, take your own individual notes on what is happening throughout.

⏳ 5 min

Q4: What was similar among the stimuli presented to the fish? What was different between the stimuli?

Q5: Make a plan for how you would collect data from the video to calculate bite rate for each stimulus. (What data do you need to make that calculation? How will you measure and record that data?).

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

Action-Specific Potential (ASP; Energy)¶

[The same principle] applies to virtually all basic behavior patterns. They will be performed spontaneously after an extensive resting period, but these spontaneous patterns will also respond to supplemental stimuli… Any given instinctive motor pattern has a specific releasing situation, which we call the innate releasing mechanism. If this situation fails to occur over an extended period of time, the instinctive motor pattern takes matters into its own hands, so to speak, through a lowering of the stimulus threshold, which can go so far that the motor pattern is performed in the absence of any observable stimulus… The internal spontaneous drive and the external releasing stimulus [(sign stimulus)] are summated.

—Here am I, where are you? pg 83-84, Konrad Lorenz

⏳ 15 min

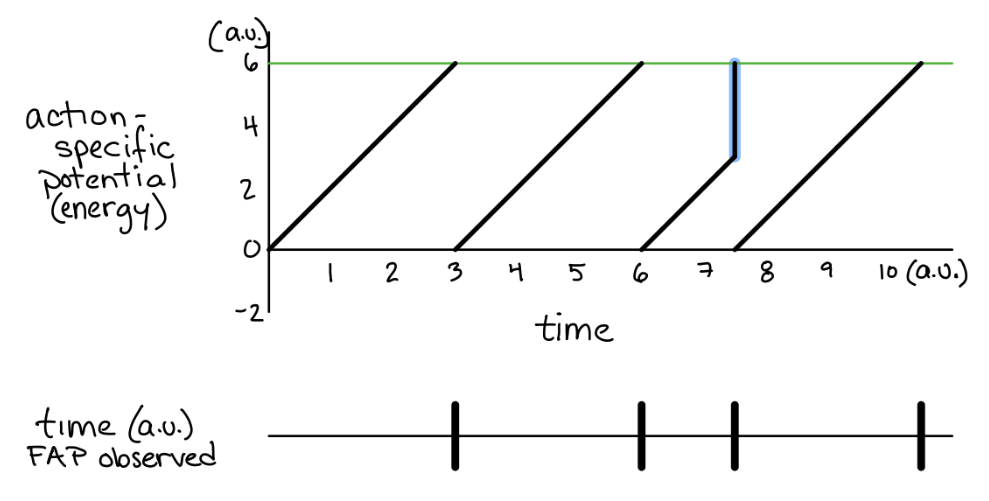

Examine the following representation of a theoretical model for behavior posed by Lorenz.

Fig. 4 Lorenz’s model of behavior in terms of FAPs and their expression/“release”. A sign stimulus is presented at time = 7.5au.¶

Q6: What three variables are represented in Lorenz’ model of behavior?

Q7: What data is being depicted in the top 2-D plot?

Q8: What data is being depicted in the bottom 1-D plot?

Q9: According to the data in the figure, what is the rate at which action-specific potential increases in the absence of any sign stimulus?

Q10: How does the data in the bottom plot relate to the data in the top plot?

Q11: How would you define the green horizontal line in the top plot using any or all of the following terms: action specific energy, time, and/or FAP expression?

Q12: In the top plot, what is different about the black line that starts at time=6au from the black lines that start at 0, 3, and 7.5?

Q13: In the bottom plot, what is different about the third FAP observed compared to the first, second, and fourth?

Q14: Based on the information given in the model and your work so far, how would you define the term “sign stimulus”?

Note that FAP’s expressed in the absence of a sign stimulus are called spontaneous.

⏸️ PAUSE here for class-wide discussion

We can think of action-specific energy as the motivation for a particular behavior (FAP). Both internal drive and external stimuli contribute to this motivation. The strength of a stimulus is defined in terms of how much it changes the action specific potential for a FAP.

As an analogy, let’s consider eating behavior. The liklihood that you will eat a food can depend on the properties of the food itself (food preferences effect eating behavior).

Fig. 5 Relationship between variation in food taste and desire to eat food.¶

Think about your own food preferences and whether a sweet food be a strong or weak stimulus for eating. Then, imagine you are are really really really hungry (ie. increased internal drive to eat), would you be more or less likely to eat in response to a weak food stimulus compared to when you are full?

Why (in terms of Lorenz’s model)?

⏳ 10 min

Q15: Complete this sentence by selecting one of the options: The more motivated an animal is toward a specific FAP, the ( higher / lower ) the action specific potential for that FAP.

Q16: Complete this sentence by selecting one of the options: The more motivated an animal is toward a specific FAP, the ( stronger / weaker ) the stimulus needs to be to elicit the FAP.

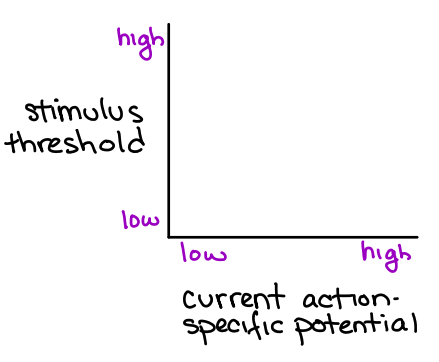

- stimulus threshold¶

the minimum stimulus strength needed to trigger/evoke the behavior

Q17: Complete the following plot to demonstrate your current understanding of the relationship between stimulus threshold and current action specific potential for an FAP.

Fig. 6 Relationship between stimulus threshold and the current action specific potential.¶

⏹️ STOP here for today

- 1(1,2)

David J.Anderson and Pietro Perona Toward a Science of Computational Ethology. Neuron 84:1 (2014).

- 2(1,2)

Datta SR, Anderson DJ, Branson K, Perona P, Leifer A Computational Neuroethology: A Call to Action. Neuron 104:11-24 (2019).

- 3

In Here am I. Where are You? (1988), Lorenz uses the term ‘instinctive motor pattern’ instead.

- 4

- 5

Historically, behaviors are considered FAPs when they are instinctual (ie. genetically-determined and pre-programmed). Lorenz used the German word ‘Erbkoordination’ which translates literally as ‘inherited co-ordination’ to describe them. In a more contemporary mindset, we can think of behavioral patterns that need not be purely pre-programmed (as you will learn in this course if you have not already… no behavior truly is).

- 6

For example, see the landing page for ‘innate behavior’ from Kahn Academy. However, note that the reference for this result is a textbook, not the original article. The data from the publication in German is not available. Based on replications of the original experiments, it turns out that Tinbergen’s results from the 1937 paper may be less clear.